Re-reading notes. Highlighting chapters. Cramming material the day before an exam. There’s a good chance your students use one of, if not all, of these techniques. One of the reasons behind their study methods? Let’s turn to sports for a helpful analogy. If an athlete wants to gain stamina, would they complete pushups on their knees or toes? Completing this exercise on their knees might be easier, but the latter method ultimately supports long-term strength. As Daniel Willingham—Professor of Psychology at the University of Virginia—believes, the majority of students learn by doing the mental equivalent of push-ups on their knees.1 Students opt for low-effort, low-involvement study methods such as rereading notes given it creates a sense of familiarity with the material. Being able to apply information to new settings is an entirely different skill.

Part of the reason why students aren’t studying effectively: they weren’t taught how. In fact, only 20 percent of students agreed that they study the way that they do after a teacher taught them how to study effectively.2 The pervasive ‘metacognitive equity gap,’ coined by Dr. Saundra McGuire—Director Emerita of the Center for Academic Success at Louisiana State University and author of Teach Students How to Learn—continues to prevent certain populations from succeeding. For instance, economically disadvantaged students often don’t have access to mentors or tutors who model metacognitive thinking skills. In addition, students from underrepresented communities are more likely to have a fixed mindset about intelligence. The good news is that the right tools paired with the right mindset can turn even the most underprepared cohort into confident learners. Here are three scientifically proven ways to turn students into conscious thinkers during the study process.

→ On-demand webinar: Dr. Saundra McGuire on teaching students how to learn

1. Turn students into leaders by promoting a growth mindset

How many times have you heard your students say that they ‘aren’t math students?’ or that they ‘aren’t as smart as their classmates?’ These are classic traits of a fixed mindset, where students attribute failure to a lack of ability. Feelings of doubt or inadequacy—often a byproduct of imposter syndrome—are even more pronounced among historically underrepresented students.3 But as Dr. McGuire reminds us, a growth mindset is the precursor to long-term success and greater confidence. Students are better able to persist in the face of setbacks and view their mistakes as invaluable learning moments. You might consider using some of the following techniques to promote a growth mindset among your students.

- Embrace the word ‘yet:’ The next time you have a student who claims that they’re ‘not a chemistry person,’ add ‘yet’ to the end of their statement. Doing so will signal that they’re able to improve upon their ability with persistence and time.

- Test more often: Give students more opportunities to show what they know and shore up their learning gaps early. You might consider increasing the frequency of tests from three per term to smaller, bi-weekly quizzes.

- Encourage goal setting: Prompt students to set SMART goals in the lead up to a test. Start by asking learners to set a broad goal (such as achieving a B+ or higher on their assessment) and then have them list the steps they’re taking to meet that goal. The ultimate end result is to signal to students that a state of growth is always possible.

- Equip students with effective study tools early on: It could be a lecture on The Study Cycle. Or providing resources on learning strategies after students complete their first test. Encouraging integrative learning begins with awareness and education.

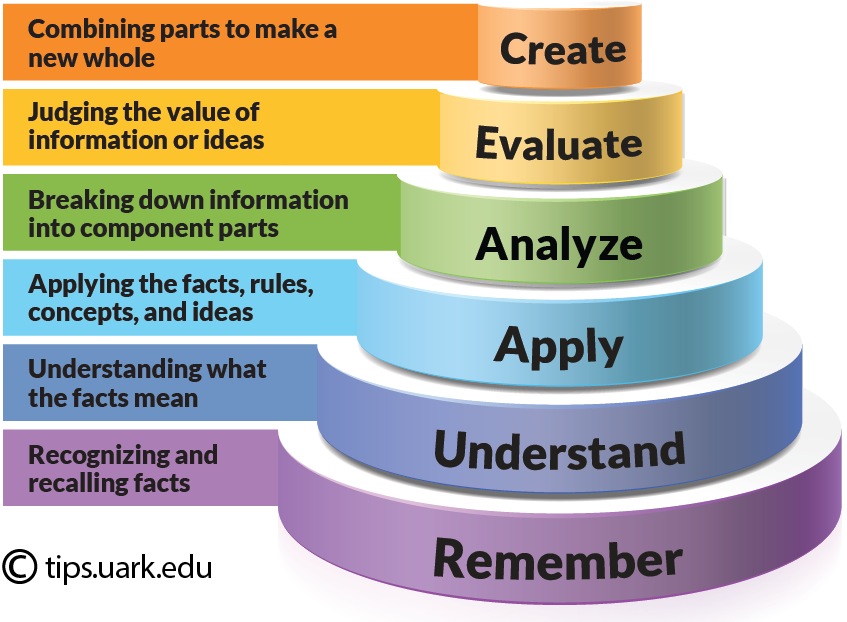

2. Help students see value in Bloom’s Taxonomy

Bloom’s Taxonomy is just as much for students as it is for instructors. The age-old educational framework is an invaluable tool in informing study methods. Helping students see the value in Bloom’s Taxonomy involves exposing the ‘hidden curriculum’—the unwritten rules and context in which learning occurs—and outlining clear expectations in the lead up to assessments. If students are to adapt their own study techniques for the better, educators must first make their class aware of how true learning takes place.

Effective studying begins by prioritizing long-term knowledge retention over rote memorization. While helping students remember and understand information has its place when introducing new material, moving learners towards applying and analyzing will better prepare students for their exams. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill offers several study methods to support higher-order thinking no matter your discipline.

- Remember: Design flashcards for key definitions or design a timeline capturing key milestones.

- Understand: Summarize a chapter using one’s own words.

- Apply: Complete problems that encourage students to relate concepts to the real world.

- Analyze: Consider how a different population might view a concept or debate how a single element relates to a broader challenge.

- Evaluate: Take a stance against an argument or consider which point of view is most effective.

- Create: Design an experiment or write a short story about a new concept.

3. Embrace The Study Cycle

Familiarity can often be conflated with understanding. Dr. McGuire advocates for a more thoughtful approach to studying—one that boosts long-term retention.

Coined ‘The Study Cycle,’ the process of acquiring knowledge is broken into five key steps. Students begin by previewing material and forming big picture ideas. Next, they actively participate when attending class, such as by answering questions and completing problem-solving activities. Third, students then review their notes and fill in any gaps in their understanding. The fourth step is where studying begins. Here students are encouraged to set a specific goal, and to study for a 30–50 minute burst by thinking critically about what they are learning. Asking ‘why,’ ‘how,’ or ‘what if’ helps students to engage more deeply with the material. Then they should step away for a 5–10 minute break before summarizing what they’ve accomplished. At this point, students decide whether to continue studying, take a longer break, or change tasks.

Focused study sessions, outlined in the video below, are structured to help students more effectively absorb (and retain) the information they’ve just reviewed. You can do this in class as well using active learning techniques such as concept mapping or asking students to teach material to a peer to gauge how well the content has stuck.

Helping students recall information beyond test day isn’t impossible. Nor does it require a massive overhaul of your course or additional hours of instructional planning. The process involves exposing methodical study techniques that won’t only serve students during their time in your course, but their entire lives.

→ On-demand talk: How to fuel academic success

References

- Willingham, D. T. (2023, April 20). There are better ways to study that will last you a lifetime. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/20/opinion/studying-learning-students-teachers-school.html

- Kornell, N., Bjork, R.A. (2007). The promise and perils of self-regulated study. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 14, 219–224. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03194055

- Le, L. (2019). “Unpacking the Imposter Syndrome and Mental Health as a Person of Color First Generation College Student within Institutions of Higher Education,” McNair Research Journal SJSU: Vol. 15 , Article 5. https://doi.org/10.31979/mrj.2019.1505 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/mcnair/vol15/iss1/5