Top Hat is the active learning platform that makes it easy for professors to engage students and build comprehension before, during and after class. This interview is part of our recurring series “Academic Admissions” where we ask interesting people to tell us about the transformative role education has played in their lives.

Samra Zafar, speaker, mentor and advocate for educational rights, knows the life-transforming power of education more than most. Promised the schooling she had been dreaming of since childhood, she married at 17 and moved from the Middle East to Canada—but then became trapped for a decade in an emotionally abusive and physically violent family who stripped her agency away. After secrecy and struggle, she finally started at university, giving her the spark of freedom she needed to escape. This is the story of how higher education saved, then built a life.

Zafar’s bestselling memoir, A Good Wife: Escaping The Life I Never Chose, is available here.

Zafar, an early lover of school, is seen here receiving the award for top student in her grade one class. “My passion for education was just in there from day one. Even on weekends, I would gather all my sisters and play teacher.”

Even as a young girl, growing up in Abu Dhabi, I was so passionate about school. I would get really upset about the one percent that I lost on a test, instead of being happy about the 99 percent that I got.

It drove everyone crazy, but it was just something that I lived and breathed—and every test, every exam was a minor milestone for me. My passion for education was just in there from day one. Even on weekends, I would gather all my sisters and play teacher. I would teach them stuff that I would learn in school, which was much higher than their grade level.

Oftentimes I would get pushback, especially from the extended family. They were like, “Oh, what’s the point of being so passionate? You’re going to get married anyway.” Or, when I would talk about my dreams of going to the top universities and doing amazing things to change the world, I was told that, as long as they’re dreams, they’re okay, just don’t expect them to come true.

But that fire kept burning, and I kept pushing back. And this theme carried through my marriage as well. My dream was to get an education and go to school. That education did a lot more for me in terms of opening up my mind and giving me the courage to eventually leave.

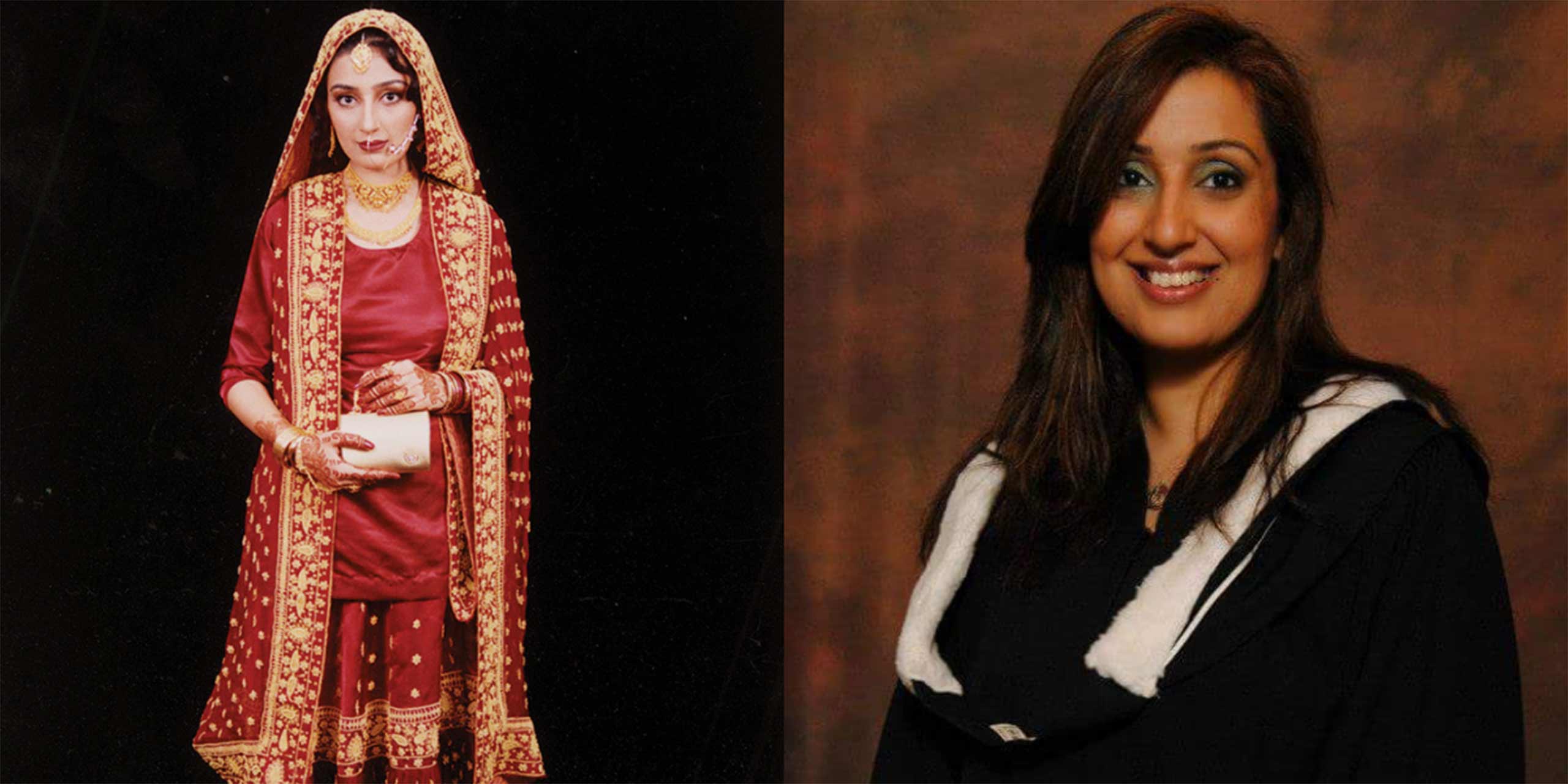

Zafar, left, on the day before her wedding, aged 17—and on the right, graduating from the University of Toronto.

Dreams snatched away

I was 16 years old when the marriage proposal was presented to me. My mother’s friend was the sister of a man 11 years older, who lived in this faraway country called Canada. She wanted me as her brother’s bride. And I said no, a few times. I tried to resist. Every time I tried, I was knocked down by being told that this was the best thing for me and I’m going to be ungrateful if I let it go. And my mom would say the same thing. Eventually, my voice was taken away. I ended up getting married to him when I just turned 17.

When I came to Canada, I thought that if I can go to school, maybe it is not such a bad thing. I was told not to think of it as marriage, but to think of it as an opportunity to go to university in Canada.

But those dreams where snatched away from me. When I came here, as his wife, I was told that I should be grateful that I didn’t have to go through all of that education crap. And that was his mother who said that to me. We were living in a joint family, with him and his parents, and I was often told that I need to get off my dreams and hobbies and silly goals because that’s not what a girl does, that’s not what a good wife is about, that’s not what a good woman is about. No matter how much I tried to fit into that box, that little voice in my head never went quiet: “I want to go to school. I want to get an education.”

I kept trying in my own ways. I finished my high school at home through distance learning because I wasn’t allowed to go to a proper high school. I applied to university and got in, but couldn’t go. I didn’t have a penny on me, my husband and his family wouldn’t pay the fee and I couldn’t get a student loan because the Ontario Student Assistance Program looks at household incomes and our family income was above that threshold—even though I had no money of my own.

I eventually started working as a babysitter at home to save every penny that I could. Once I had enough funds to pay my own fees, I applied again to university: after ten years of marriage and two children. All the while, I was being told by my husband and his parents that I would lose my children if I left the marriage, because I didn’t have a job or an education, that no one would support me, and that I’d be used property or damaged goods. But these lies kept me trapped in that cycle of abuse.

University of Toronto at Mississauga, Ontario, Canada. Photograph: Public domain

All those nets were broken when I started going for counseling at the University of Toronto (U of T). I would skip class to go, because I didn’t want my husband to find out that I was staying late at school. My world really started to open up when I learned about my own self-worth, and I decided that I needed to break that cycle. I learned what was happening to me at home was abuse and it was not okay and I did deserve better. I learned that I had rights as a woman and as a human being. I didn’t want my daughters growing up thinking that their family was normal and accepting the same behavior in their own lives. So I decided to leave, I took my daughters and I moved to U of T at Mississauga (UTM), to on-campus housing. For the next couple of years, I was working four or five jobs, raising the girls and going to school full-time. I eventually graduated as a top student with scholarships and awards—and I went on to do a master’s.

“Who are you?”

In my university days, in my very first year, I was still married, working as a babysitter at home but going to school and taking one or two classes. I met with a prof, James Appleyard, because I got 19.5 out of 20 on one of the tests. I went to him to argue about why did I lose that 0.5 because I didn’t think it was fair. He agreed with me, gave me that half mark, then said, “I have never had a student who’s come to appeal on a 19.5 out of 20. So who are you?” I told him about myself, and he was just warm, caring, empathetic, nonjudgmental and supportive. I ended up sharing what was happening to me at home, and he really gave me a lot of great encouragement. He wrote a letter for me for a couple of my scholarship applications.

There was another professor, Gordon Anderson—I remember I had trouble even going up and asking him a simple question about tutorials. And I thought, why would this legend of a prof talk to me? I’m just a nobody and somebody not worthy of attention or respect, because that’s what I was being told at home everyday.

Later on, once I was finally living on UTM campus housing, I ended up becoming his TA, and then he promoted me to head TA. He’s in my life, even to this day. He’s retired now, but we keep in touch and I talk to him quite frequently. He has been an incredible mentor and support system to me.

I also won the John H. Moss Scholarship for student leadership, which goes to one person annually from all of the U of T campuses. When I applied and reached the final shortlist, I was interviewed by a panel of industry professionals and U of T alumni that are extremely accomplished. That panel was headed by John Rothschild, the CEO of Prime Restaurants. I reached out to all the people on the panel, including him, to ask them for coffee and he said, let’s do breakfast. In the past six years since then, I have had countless breakfast and lunches and dinners, and I would say he is my biggest mentor.

L-R: Former U of T Alumni Association president Matthew Chapman, former U of T president Dr. David Naylor, Samra Zafar and the Honorable Michael Wilson, then chancellor of U of T. Zafar won the John H. Moss scholarship for student leadership at the University of Toronto—opening doors and strengthening her community of supporters. Photograph: Gustavo Toledo Photography

Samra Zafar and her mentor, John Rothschild, CEO of Prime Restaurants. “I wouldn’t be half the person I am today if it weren’t for his constant guidance and support.”

I wouldn’t be half the person I am today if it weren’t for his constant guidance and support. After my kids, he’s probably the most special person in my life—almost like the dad that I never had. The one thing that inspires me the most about him is that he’s not apologetic about his success at all, but he is still the most humble person that I have ever met. When he talks to anybody on the street, no one can tell that he is that accomplished, and he is just so passionate about giving back and helping others. He mentors hundreds. I’m lucky to be one of them. I have learned so much from him and he really helped me believe in myself. I’m in awe of his strength and humility.

Breaking the silence

My advocacy for education really started when I began sharing my story, back in 2013 after I won the John H. Moss Scholarship and when I met John Rothschild. I felt like there was something that I needed to do with my story—so I shared it [in the Express Tribune, a prominent international Pakistani online newspaper] and it went viral. And a lot of people, especially women around the world, connected with it. I started mentoring women who would reach out to me: I’ve mentored at least 35 women over the past five or six years. It’s amazing to see the successes that they’ve accomplished, whether it’s going back to school or starting a new business, or increasing their self-confidence or establishing a new support system.

Half of the conversation about domestic abuse is breaking the silence. You’ve got to talk about the things that are happening in your community, your family, your living room, wherever. The other half is to support survivors: when people come forward, believe them. Do not shame them, support them. Act with empathy and kindness. Empower them to believe in themselves. And that is so, so, so priceless.

Education and awareness, I would say, are the most important pieces in terms of actually moving forward for change. You’ll see something in the national news all over where somebody kills his wife. But it’s not like somebody wakes up in the morning and decides to just murder his wife that day. The abuse started years and years ago, but why didn’t anyone talk about it then? Why did no one come forward? Shame and stigma, and also, lack of awareness. So many women don’t even know that they’re being abused because the scars are invisible. The scars are on their soul. Abuse is not about slaps and kicks, abuse is about control. And control can be exerted in many forms, including with loving words and romance, because that’s the way to entrap the victims.

We need to start talking about what healthy relationships even look like, especially with children who are not seeing good examples in their families. They need a counternarrative that is more positive, coming from schools and teachers and other people around them.

I know that my story is not just mine, it is the story of millions of women and girls around the world. There are 12 million girls every year who are forced into child marriages. One in three women in Canada have been affected by domestic abuse. One in two women in Canada have been affected by physical or sexual assault at some point in their lives. And that’s not okay. There are 6,000 women every single night who are turned away from shelters that are too full. There are children who suffer from mental illness for so many years because of exposure to domestic abuse when they were younger.

There’s far too much silence around this. People brush it under the rug, leave it behind closed doors and stay hush because it’s too taboo. But until we can remove the taboo from these conversations, how is change going to happen? The biggest ally of abuse is violence and shame. Shame is what creates silence, and silence is what creates shame. They go hand in hand. But the shame doesn’t lie with us. The shame lies with the abusers. And unless and until we speak up and start changing that narrative, things are not going to change.

Choosing your family

When I look back and ask myself, what was the game changer in my life, it was the community of support that I found at UTM. While I was a student, I made friends who could watch my children when I went to class or court. My professors helped me believe in myself and spent hours motivating me. My mentors helped me make critical decisions along the way. My counselors just saw me as a person who was trying to build a better life, and rallied around that. That feeling of “I’m not alone and I don’t have to do this alone,” is priceless.

And that’s what people need. Especially when you’re in a strange country and you don’t have a lot of support around you, you need people who will champion you, who will believe in you—because that can turn into you believing in yourself. The story I tell is not about me—it’s about the power of humanity, human connection, and how being surrounded by positive people who believe in you helps you build resilience. Because their voices will resonate with that little voice in your own head which says, “I can do this.” You keep putting one foot in front of the other, you look back and you’re like, “Oh my God, I got this far.”

Education is not about being career ready. It’s about being life ready. So I do not practice as an economist, though that’s what I studied at school. But, the critical thinking, the learning of the ability to build connections, the ability to talk to people, confidence and all of those things that I have gained through education have set me up for success in my life. It’s something that no one can take away from you—that is so priceless. So never take education for granted. Really realize that you’ve got the power instinct in you to build a life and create it the way you want.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity. Additional research by Harleen Dhami.