Top Hat is the active learning platform that makes it easy for professors to engage students and build comprehension before, during and after class. This interview is part of our recurring series “Academic Admissions” where we ask interesting people to tell us about the transformative role education has played in their lives.

Tony Bates almost never made it into higher ed. Told his grades weren’t good enough by a snooty English headmaster, he joined the workforce as a clerk before a fortuitous meeting put him on the path to a psychology degree at Sheffield University. Focused on educational research, Bates soon found himself drawn to finding the best use of multimedia in distance learning. Since then, Bates has written a dozen books on distance education and online learning and consulted in 25 countries for the planning and management of online learning. He’s currently a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education and Training Network and a Senior Advisor to the Chang School of Continuing Education at Ryerson University. His grades, it turns out, were definitely good enough.

Let’s get this straight: no one ever says, “When I grow up I want to be an educational technologist.” It’s something I drifted into. I had bad advice when I graduated from high school in England. I was told by my headmaster (an Oxford man) that my grades weren’t good enough for a prestigious university. At that time my mother was a single parent and we had very little money, so I went out to work. After two mind-numbing years as a bank clerk and a filing clerk, I was desperate. I went to the city council (London County Council at the time) to see if I could get a grant to study at a teachers’ training college. When I got to the office the desk clerk was at lunch. A manager came out and asked what I wanted. He asked for my grades then asked why I didn’t want to go to university. I told him and he laughed. “You can get into any number of state universities with your grades,” he said. “When you’re accepted, the LCC will cover your costs.” The kindness of this man who took the extra trouble during his lunch hour turned my life around.

I studied psychology as an undergraduate at Sheffield University in the UK. When I graduated, my professor, Harry Kay, asked what I wanted to do. I said “Educational research—to learn how people learn.” He told me I’d better teach first, so I’d know what I was researching. It was good advice. I took a post-graduate diploma in education at Goldsmiths College, University of London, then spent three years as a teacher in primary and secondary schools in Worcestershire and Birmingham. Eventually I got a job at the National Foundation for Education Research looking at the administration of very large high schools—”comprehensives”—that had just been established by the government. I used that research towards my PhD at London University. The NFER job was a three-year contract so when it ended in 1969, I applied for a job as a research officer at the newly established British Open University, which was a radical experiment funded by the Labour government to use distance learning to reach non-traditional students.

A clip from an Open University lecture, which aired on British TV in 1973.

I was hired to study the effectiveness of distance education, and as part of that work I evaluated the television and radio programs that the BBC created for the Open University. That’s what got me interested in educational technology. I found that students responded differently to the TV and radio programs than to the print materials, which led me to look at how students learn, and how they approach learning from different media. I eventually became a professor of educational media research.

The eye-opening potential of online learning

In 1984 I went to Vancouver to give a keynote at a conference. A Canadian colleague invited me to his home, and then down to his basement. I was a bit suspicious, because I didn’t know this guy very well, but down I went. He said, “Look, just watch this. I’m going to log in and we can talk to somebody in New York via the computer.” And what it was, of course, was the first iteration of the Internet. It was a typed conversation, an early email, and eventually I asked the person at the other end, “How old are you?” He said, “13.”

Well, there are two things with that: first of all, what was a 13-year-old doing up at two o’clock in the morning in New York? Never mind. But the second thing was, it didn’t matter that he was 13, we were all equal in the conversation, and I felt that was groundbreaking from an educational point of view. It was open access. And it opened my eyes to the potential of online learning.

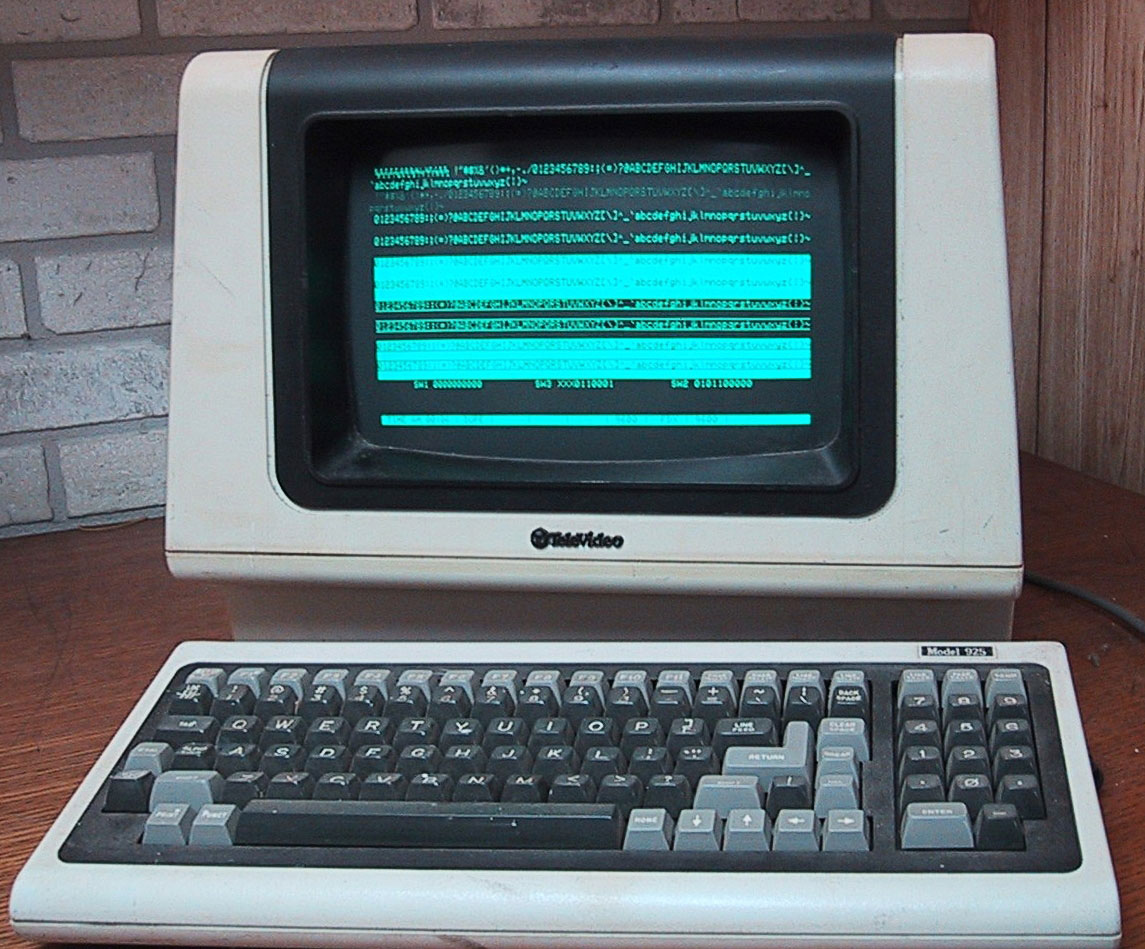

A “Televideo 925” Terminal for communication, built in circa 1982. Photograph: Public Domain

Up to that point we had computer assisted learning, but it was behavioristic—tests of comprehension and automatic grading. And that was fine for teaching certain things, but the idea that you could use computers to enable people to communicate at any place, at any time—from an educational perspective, I thought this was terrific. I went back to the Open University and we tried to get online learning built into some of our courses. But it was slow-going, and I soon got frustrated there and I felt I could do better in Canada.

I moved to Vancouver in 1989 with the help of Glen Farrell, who was the President of the Open Learning Agency—he was someone who directly influenced the trajectory of my career. The mission of the OLA was to provide accessible and varied courses that could be taken anytime and at an individually determined pace. I headed up research, strategic planning and international development. After five years I was approached by the University of British Columbia, which had recently received a $2 million dollar grant from the government to introduce technology into its teaching. Dan Birch, who was the provost, thought I could help them, and that was a really good move for me.

I became a director of distance education and technology, and helped UBC move toward technology-based teaching and learning, both on campus and at a distance. As a result of the government grant, the noted Canadian educational technologist Murray Goldberg was able to develop WebCT, which became the first LMS (later bought by Blackboard). We set up some of the first fully online courses in Canada, and one of the first fully online Master’s programs. In 2003, I retired and set up my consulting business, and today I continue to help post-secondary institutions to plan, manage, develop and deliver online learning and distance education.

What students need: Experiential and problem-based learning

An example of a table setup for an active learning classroom.

Here’s the thing: over the course of my career I’ve seen that technology keeps moving forward, but the basic teaching methods are stagnant. And that’s a huge problem. Universities still practice a kind of information transmission model—lecturing, and so on. But that doesn’t help students develop critical thinking. It’s imperative now more than ever that students have high level intellectual skills, because artificial intelligence will eventually handle everything else. So in order to help students develop essential skills, you have to get away from just delivering content one way.

You have to give students opportunities to practice their skills, you have to give feedback on their skills, and that means adopting different teaching methods. And yet, professors and instructors are locked into a system. Lecture theaters and traditional classrooms with rows of seats facing the front make it very hard to teach in another way. And what we want, of course, is students coming in having done work at home, able to project that work onto screens around the room, working in small groups, getting feedback from the instructor in class about what they’ve done online. Students need experiential learning and problem-based learning.

There’s another side to this problem. What I’ve seen, over the last 30 years, is that teaching has become less and less critical for a professor’s career development. Research is the driving factor. It’s not that they don’t care about teaching, but teaching doesn’t get them advancement, it’s pulling in the research grants that brings on promotion. Most faculty don’t have any training in pedagogy—the institutions don’t require it—and without that it’s really hard to change your teaching methods. And without changing the teaching methods, it’s really hard to exploit the technology that’s available to us. There’s a chain reaction there, and we’ve got to break that tradition and find ways to train faculty and get them to teach in more learner-centered ways that support skills development, as well as content acquisition.

Digital literacy is more important than ever

I started my career delving into how students acquire content and knowledge. Today, it’s crucial to train students in knowledge management so they know where to find information, how to evaluate it, how to judge its value. We have all kinds of sources of information, many of which are totally unreliable or deliberately misleading, so our students must be reflective and evaluative in how they approach sources of knowledge. That’s a specific skill, but it applies to all subject disciplines.

I’ve spent my career arguing for digital literacy in post-secondary academics. But the way I see it, it’s never been more important than in the last two or three years.

It’s hard to think of a subject area now where you wouldn’t want a student coming out who is digitally literate, so they know how to use digital technology appropriately in whatever discipline they’re in. We should be educating them to survive in the digital age and prosper in the digital age. And that may mean setting up their own company, or being entrepreneurial, or going into a traditional company and changing things to help that organization survive.

I’ve spent my career arguing for digital literacy in post-secondary academics. But the way I see it, it’s never been more important than in the last two or three years. All of these issues around data privacy, security issues and misinformation mean we must require students to understand how their data is being used and how technology is used and exploited.

I see the public higher education system very much in the same way as climate change; there are massive changes happening and there’s very little time to put it right. But we can do it. We need people who can provide political leadership, senior management to show leadership, and maybe not every instructor, but key instructors, key faculty in each university who see the need for change and will help lead it. But you also need strategies for digital learning and achievable targets that will survive over changes of personnel. Business does that all the time; higher education must take up the challenge.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.