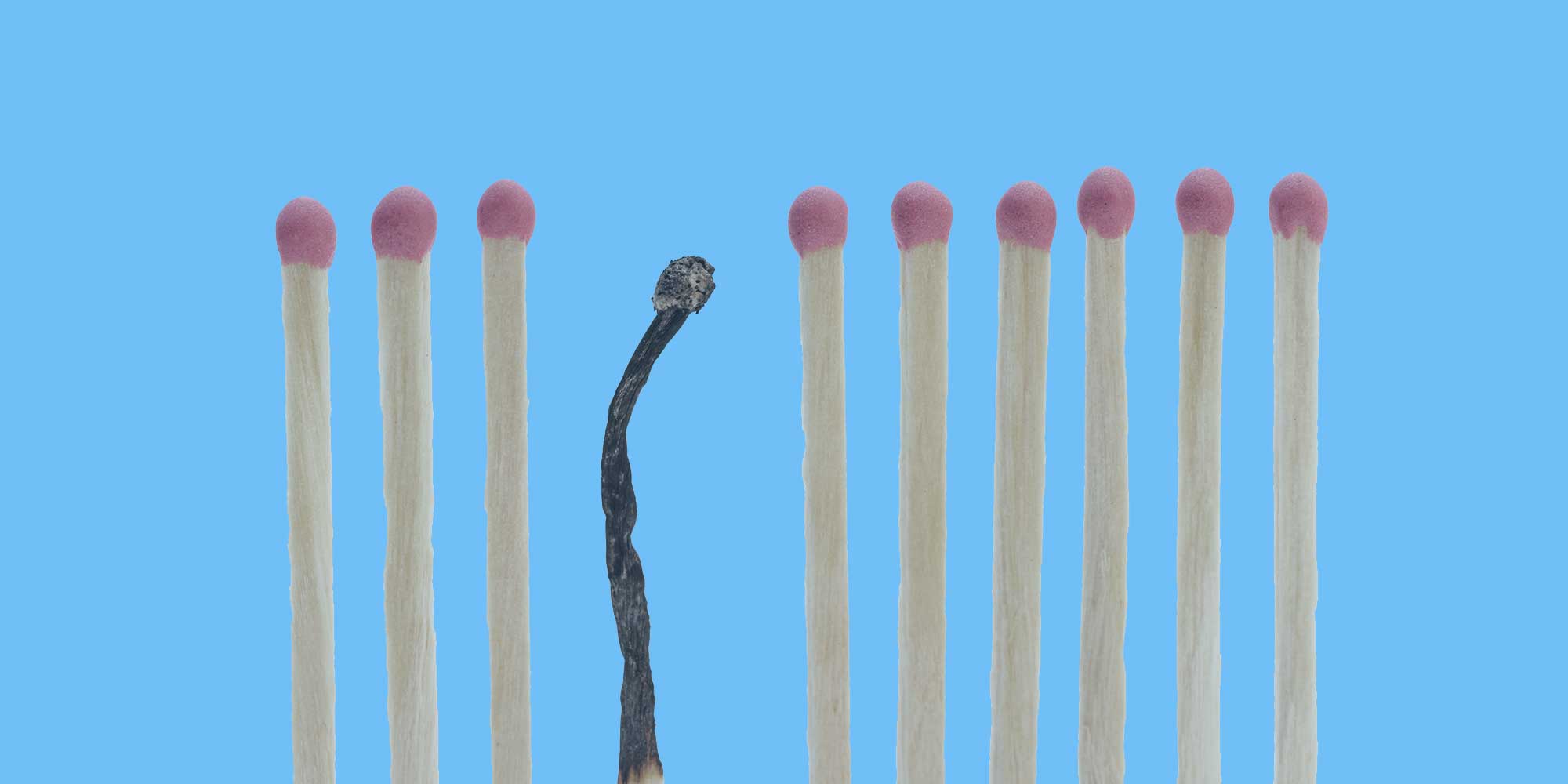

Most faculty aren’t doing what they do for the money: it’s a vocation. But when you do what you love—and in particular for adjuncts, for little stability or monetary reward—it’s extremely easy to get overwhelmed and burn out.

May is Mental Health Awareness Month, and one of the major focuses in 2019 from organizers Mental Health America (MHA) is work-life balance and burnout. The mental and physical health impacts of workplace burnout and stress are estimated to cost as much as $190 billion per year—or $6,025 per second—in healthcare spending in the U.S., according to MHA. Furthermore, poor work-life balance increases your risk for health conditions like sleep problems, digestive disorders and mental health problems.

Here are some perspectives from professors of different career levels writing on Quora, who are dealing with burnout and related problems—from too many responsibilities, to anxiety and overwork. It’s to say that if you’re experiencing similar problems, you’re not on your own.

Steve Schwartz

Adjunct, Bridgewater State University

I always wanted to do research on the natural world. I enjoyed graduate school with less emphasis on classes, the opportunity to do research, and the collegiality of like-minded individuals. Even as a postdoc I ended up in a wonderful place with great people to be around and the freedom to look at the world in all sorts of new ways.

Then reality set in. It took too many years to get my first job, at a small school in a small town, with a heavy teaching load, no graduate students, little funding for research and little space to do the research if there was some money. Colleagues in other departments were jealous of our “reduced” teaching load because we were given credit for teaching lab classes that lasted three hours. The result—I burned out within a few years. Therapy ensued as I dreaded the start of each semester.

Now, I have been a teaching adjunct for the past 12 years. I have done zero research as there is no money or space. I am burned out on teaching and tired of dealing with non-majors every semester. Pretty much all the fun has gone out of it. I have to do it to make a little cash—adjunct pay is horrible.

For those who have been able to follow their dreams, there is no burning out. For the rest of us, burning out is inevitable.

The more senior we get, the more work tends to come our way

Ben Y. Zhao

Professor of Computer Science, University of Chicago

Being a professor at a top university is stressful. I saw it in my faculty advisors at Yale and Berkeley, and I felt it first hand as faculty at UC Santa Barbara (assistant, associate, then full professor) and now at the University of Chicago (chaired full professor). But then again, so is any other highly competitive job. Certainly, if you make it this far along, then you’ve been trained through experience on how to handle the stress well. So it is stressful, but we all have our own ways of handling it. Some approaches are not very healthy, and can lead to early burnout or disruptions in the non-academia parts of your life.

I will say that in general, faculty at top schools have far more work than there is time to do. There is no efficient schedule that we can come up with to actually get everything done. It’s generally impossible. Instead, our scheduling algorithms are more like prioritization algorithms, with the full knowledge that low priority items are likely to be ignored and forgotten.

The more senior we get, the more work tends to come our way, and the more things fall off our plate and onto the floor. The number of “Hi, did you get my email about XYZ, because you never responded” e-mails I’ve gotten has dramatically increased over the years. A common piece of advice between faculty is that we all (and especially younger faculty) need to learn to say “no” more often.

The work is quite literally unending

Christine Lloyd

Lecturer, Everett Community College

I teach at the community college level, so I have it “easy” in some ways (almost never have to deal with parents, curriculum is less mandated from above, depending on my schedule I may only teach two hours in a given day though I might also teach six on others).

But the work is quite literally unending.

Have I finished grading this week’s assignments and quizzes? Do I have the quizzes written for next week? Are my slides ready? Which activities are we doing? Do I have all the pieces I need for them? Did I make the assignments in the online learning system and write the rubrics? There’s an exam in two weeks, have I finished writing the practice questions and the key? Have I finished writing the exam? What about that question a student asked in class and I said I’d get back to them because I didn’t know the answer, have I researched that yet?

I am continually in a state of wanting more hours to spend than there are waking hours in my day. Something has to give, so I cut it back to what feels like the minimum, and every quarter I hit a point around halfway to three-quarters of the way through the term where I realized I overdid it and something has to give. So I do my best and it isn’t all that great anymore, where I take a week (or more) to grade assignments and quizzes, where my slides in class are walls of text instead of the pared-down slides with pictures I like.

Katerina Kaouri

Lecturer in Applied Mathematics, Cardiff University, Wales

It can be quite stressful. Professors are indeed teachers and they should do this job well but this is only part of their working time. They should also produce excellent research, so uncertainty and hard work fills their days because you do not know where research will take you and if you are going to have a paper worthwhile publishing to a good journal.

On your research output you mainly base your applications for funding which take up a lot of time but have very low chances of success as this is a very competitive game. For example, all my August will be mainly spent writing an EU proposal with a very uncertain outcome. Add to these all the meetings and travels to talk about your research and discuss it at conferences and in other universities and elsewhere—quite a bit of preparation is needed generally for those presentations.

Adding all this together sounds like no free time exists. However, I believe relaxing is essential, preferably by doing sports (although I do not exactly follow what I advocate and I usually watch a TV series—although I do walk to my work and back.)

Overall, I believe that an academic cannot work less than 50 hours per week—many times more.