Neuromyths are commonly held false beliefs about the brain that can be damaging if they take hold in the classroom. The reason? Once neuromyths gain traction, it’s often difficult for people to separate fact from fiction. The term “neuromyth” was actually first coined in a 2007 OECD report, which declared that 50 to 80 percent of what teachers hear about the learning brain is just not true.

It’s for this reason that Harvard University Extension School professor Tracey Noel Tokuhama-Espinosa believes that learning scientists, like herself, play a strong role in helping educators make decisions about changes in their classroom. The fundamental starting point is to get rid of the myths. But getting rid of myths is not as easy as it sounds. “Even if I show you a bunch of evidence, you still want to believe what you have always believed,” says Tokuhama-Espinosa. “All the good science we have to share will get washed out because it’s going to go through the filter of prior experience, including beliefs, and many of those things are not true.”

To expose some of the worst myths, we talked to Tokuhama-Espinosa, who’s also an author of eight books on mind, brain, and education science, which is the intersection of neuroscience, psychology and education/pedagogy. She shared some of the biggest myths about the brain, why we seem to want to believe that they’re true, and why even professors aren’t immune to them.

Myth 1: Everyone has a different learning style

Fact: Learning styles pigeonhole students

According to Tokuhama-Espinosa, the theory of learning styles is actually the most costly myth. “Universities spend so much time and money on learning style inventories—on something so silly that pigeonholes people and limits their potential,” she says. “Once you’ve been told you’re a visual learner, do you know what you do for the rest of your life? You spend your energy looking for visual cues. This means it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. In truth, the brain would actually prefer to receive as much information as it can handle from all of the senses, not just the one you were labeled with.”

In 2012, Rohrer and Pashler conducted a major study for the American Psychological Association examining literature surrounding learning styles. The conclusion? Investment in learning styles inventories is a huge waste of resources. “Learning styles damage a kid’s potential,” she says. Being told you use one sensory modality more than another limits your potential for learning. It’s terrible.”

Myth 2: Online learning and face-to-face learning are equal

Fact: Online learning is far superior when it’s done well

The Online Learning Consortium has long documented perceptions of online learning. Currently, around 60 percent of people still think that online and face-to-face learning are equal. “But the best learning, according to university students, is blended—when you have a little bit of face-to-face and a little bit of online,” Tokuhama-Espinosa says. “But just below that is 100% online.” Face-to-face learning rates are lower than those of online learning because online platforms offer more resources, more flexibility time-wise and greater differentiation.

In Tokuhama-Espinosa’s online class at Harvard University’s Extension School, every module has a mini library because graduate students, undergraduate students, and people who have never taken an online course have very different entry points to the material. “I also talk fast, I know that,” she says. “But my students can stop and rewind me because I flip my classes so all of the content is delivered in a video beforehand. This means during the live class, we can dive into what the students want to know rather than passively listening.”

Tokuhama-Espinosa also teaches a huge number of students who are second language learners, so online learning helps her serve a wider population. “Technology now allows for greater accessibility by a wider audience at a lower cost,” she says. “And all of those things—flexibility, time, cost and differentiation—make online learning far superior in my mind.”

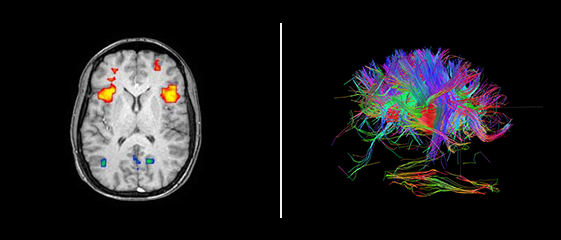

The image on the left shows a rudimentary scan of the brain done using fMRI; the image on the right offers a more advanced look at modern brain imaging capabilities

Myth 3: We only use 10% of our brains

Fact: This is the oldest neuromyth

You’re forgiven for thinking you only use 10% of your brain. The reason this myth persists? “Back in the early 1980s, neuroimaging technology was very rudimentary. So when a subject was, for example, asked to list all the animals that start with the letter D while being scanned by neuroimaging technology, it would only show an isolated part of the brain being triggered, because we only had the ability to look at certain electrical pulses.”

But now, with more complex technology that uses multiple kinds of imagery, we know that all of our thinking is made up of literally thousands of synapses firing at the same time—and that nothing we do is located in a single hemisphere, but rather in dozens of networks throughout the brain. Now we can say it’s much more than 10%, but we can’t really quantify how much.

Myth 4: Intrinsic motivation is driven by external reward

Fact: The key to motivation is personal satisfaction

In the simplest psychological sense, we know that people can be motivated positively or negatively, and that they can be motivated intrinsically or extrinsically. It’s possible to learn positively-intrinsically, negatively-intrinsically, positively-extrinsically or, negatively-extrinsically, but one is better for transferring learning to new contexts.

“When you learn something because you want to do it, there’s a higher probability of transfer, which is the real test of learning,” says Tokuhama-Espinosa. “If I learn something extrinsically and negatively—for example, you could force me to learn verb conjugation in German—but I don’t use that in a new context, I’ll pass the test and never use it again.”

“Professors have the power to make students fall in love with a subject. Passion is contagious.”

Neuroscientists know that positive intrinsic motivation is the most beneficial to learning, but most professors have a hard time embracing this fact because it means they have to personalize learning. This is a relatively new part of many professors’ job descriptions and most have a hard time making the time to get to know their students well.

If you looked at teaching 60 years ago, a professor’s job was to go into the classroom and deliver information. Knowing a lot of things others didn’t know gave you a place in academia. But the dynamics of society have changed. “Technology has now made it possible to know everything. And so the teaching and learning dynamic has to be different. It has to be engaging,” she says. “Professors have the power to make students fall in love with a subject. Passion is contagious. If you entered a class not liking the topic but have a professor who loved it, you can begin to enjoy the class, thanks to social contagion. People become better learners in environments where they feel that engagement.”

Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa is an author and professor at Harvard University’s Extension School and an educational researcher affiliated with the Latin American Social Science Research Faculty (FLACSO) in Quito, Ecuador. Her book Neuromyths: Debunking False Ideas about the Brain details more than 70 misconceptions about the brain that persist in education.