Top Hat is the active learning platform that makes it easy for professors to engage students and build comprehension before, during and after class. This interview is part of our recurring series “Academic Admissions” where we ask interesting people to tell us about the transformative role education has played in their lives.

Growing up just outside of New York City, Lauren Herckis spent her childhood surrounded by diverse communities—in her high school class, there were more than 50 languages spoken in the homes of her peers. That exposure to new ways of seeing people and the world ultimately led to a lifelong interest in anthropology and community interaction. As Herckis made her way through grad school, she had a realization about a community of her own: Neither she nor her peers had been taught anything about teaching, but now they were expected to do it effectively. So she started teaching classes on university teaching to doctoral candidates and delivering workshops to graduate students who anticipated a career in academia. She tried to disrupt academia’s echo chamber by focusing on the importance of student and faculty feedback and helping educators manage change. Today she’s an anthropologist at Carnegie Mellon University, researching campus culture, organizational change and the way that institutions and individuals engage with ideas about effective teaching using educational technologies. Here, she discusses how diversity shaped her worldview, why we should embrace change and the best ways to support faculty at different stages of their career.

My parents always told me that going to college would set me up for a life of success. A lot of my friends didn’t get college degrees. But in my family, education—in any form and by any means—was considered essential.

I grew up in Stamford, Connecticut, which is a commuter city right outside of Manhattan. My dad worked in the city, and I went to a high school that was shaped by the ebb and flow of immigration in and out of New York. There were more than 50 languages spoken in the homes of students in my graduating class. I didn’t think about how influential that diversity was until I went to college.

I arrived at the University of Michigan in 1995 planning to study aerospace engineering. I’ve always been fascinated by astronomy and physics, and interested in how things are built and used. Engineering seemed like a good way to explore that. Michigan required engineering undergrads to choose a series of humanities or social science electives, and I picked anthropology. Compared to my earlier experiences in school, college felt much more homogeneous to me. Whereas my college peers were suddenly being exposed to new ways of seeing the world and people with different backgrounds, from different countries of origin or language or religion or race, I had grown up with that. In retrospect, I think that’s why I was drawn to anthropology.

Early influences

I took a class taught by one of the big stars of anthropological archaeology. He gave these incredible lectures about the way communities change over time and shape their environment, or how the environment shapes communities, and the interplay between innovation and culture. His lectures were so evocative. He’d walk into the classroom at the last possible moment, and stare at his feet the whole way up to the podium. He’d then look up at the ceiling and talk for 50 minutes, and then shuffle back out of the classroom, never once making eye contact. And still, the story he told was so engaging! It captured my imagination.

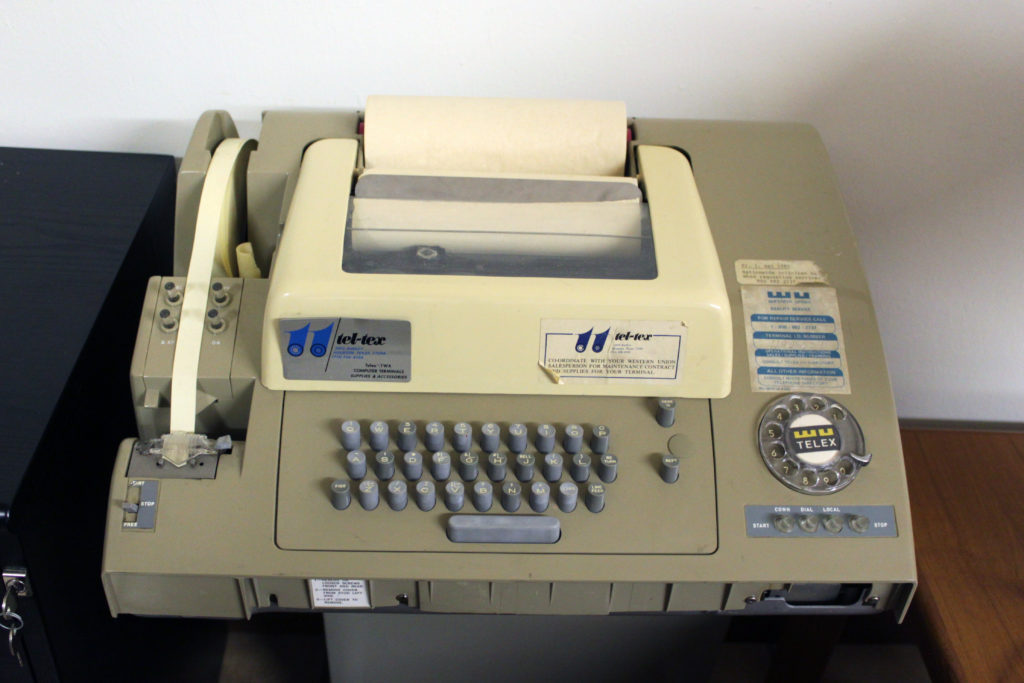

My father worked in international shipping, negotiating contracts between people who owned ships that could transport huge amounts of commodities around the world, and the people who were shipping goods. So he thought about global connectedness a lot, and I unwittingly absorbed that from a young age. We had a Telex machine in my house that spat out ticker tape. And my dad would get phone calls from Europe and Asia at all hours of the night, which blew my three-year-old mind.

An ASR-32 Telex printer.

The fact that my father, in the early ’80s, could be having a conversation with someone in Japan during their daytime was crazy to me. We had an IBM 5150, one of the early desktop computers, and I played around with early modems to connect to bulletin-board systems. Global connection and the way communities depend on one another was fascinating to me. So thinking about the different ways communities engage with their environment and how they develop cool technologies felt like a natural and familiar course of study.

An early desktop computer: the IBM 5150.

Teaching teachers about teaching

After two years, I switched my major from engineering and graduated from the University of Michigan in 1999 with a bachelor’s in anthropology. I’d known what I was going to do with my degree in engineering, but I didn’t have a plan for a degree in anthropology. There were a lot of different things I was interested in, and a handful of things that I was either good at or willing to work hard to become good at. I got a job with the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan, and volunteered in labs at the University of Michigan’s Anthropology Department over the next couple of years, learning cool applications of anthropology and archaeology. I volunteered on field projects and worked on other people’s research before deciding that I wanted to get a PhD in anthropology and look for answers to my own research questions.

I clearly remember calling my parents and saying, “I’m going to be teaching next semester!” And they said, “Okay, but how do you know how to teach?” And all I could think was, “Oh no.”

I did my graduate studies at the University of Pittsburgh. Grad students are often teaching assistants, and I’ve always enjoyed teaching and learning as part of the way I go through the world, so I was excited by the opportunity. I clearly remember calling my parents and saying, “I’m going to be teaching next semester!” And they said, “Okay, but how do you know how to teach?” And all I could think was, “Oh no.” It wasn’t a question that the professors or my fellow graduate students seemed to be contemplating. Or if it was, then it wasn’t something we were talking about. But I knew I had no idea how to teach.

So while I was studying and writing my dissertation, I got involved with the Center for Teaching and Learning, to understand how to best use all the teaching tools at my disposal. Though it was not required to take workshops or use their services, it was a resource that was available. I saw it as a pathway to an additional education, alongside my doctoral training. And it was fascinating and rewarding to learn how to teach effectively.

I received my PhD in 2015, and by then I had been the coordinator of teaching assistant services for two years. I taught a seminar for doctoral candidates on university teaching and delivered workshops for graduate students who anticipated a career in academia. And then an opportunity came up at the Simon Initiative at Carnegie Mellon, which is a cross-institutional unit focused on measurably improving learning outcomes. It was a perfect fit that brought together all of my interests.

Feedback can help drive positive change

My research revolves around trying to understand campus culture and organizational change, and the many ways that institutions and individuals engage with ideas about effective teaching with educational technologies. One incredible thing about many post-secondary institutions, particularly in the U.S., is that faculty are often teaching in isolation. There’s rarely another instructor or pedagogical expert sitting in the classroom giving them feedback. Most post-secondary instructors can spend decades teaching and never receive any meaningful feedback. Most professors do get student evaluations, but those are complicated by a lot of different factors, not least that students don’t usually know how to teach, and don’t always recognize when they’re learning.

Instructors teach based on their own experiences. And the last time they sat in a classroom as a student invested in learning the material or passing the class was probably when they were graduate students. And that means that anything that’s changed in the years since then, they haven’t experienced from a student perspective. For example, in one of my classes I asked the students to keep a 24-hour log of every communication that they had. So if they went to a store and bought a pack of gum and they spoke to the cashier, that counted. If they sent a text message to their roommate, that counted. If they posted a response to a YouTube video, that counted.

We talked in class about the different kinds of communication and connectedness that they experienced in those 24 hours, what motivates those kinds of communications and what constrains them. It was so interesting for me. Here I am teaching a class of 18- to 21-year-olds, and they communicate in ways that I could not have conceived of. One young woman promised her mom that she would be in contact every day. The day that she was keeping her log, she sent her mom a picture of her feet as she walked to class. No comment, no words at all, no content other than an image of her feet on the sidewalk. And that’s the way she’s communicating. Which is amazing. It’s got a level of intimacy and is a kind of communication that wouldn’t have been possible when I was a freshman in college. And in another five years, things will be different again. It was really fun to talk about communication and connection with a group of students who are steeped in different types of communication technologies than I am, and to hear their perspectives on what these different kinds of interactions mean.

As long as people have been innovating there have been people who can’t see how change is even possible. But change is inevitable.

Students come into universities with new experiences and expectations every year. But it’s not just the students who change. There’s the institution itself—it takes a long time to make a decision about adopting a new technology, like a learning management system for example, and then to push it out to an entire campus, let alone a whole suite of campuses. The infrastructure, the physical plant, the technological ecosystem, the kinds of support for faculty at various stages of their careers…these also change from year to year. But they change at different rates. We see the changing lives of our students because it happens so fast: New fads, new tech and ideas every year. Faculty expectations change slowly, and institutions change even more slowly. Identifying the barriers—and the opportunities—to make positive changes in postsecondary education requires that we contend with the intersection of culture and innovation. It requires that we take into account these very different paces of change. That’s what I grapple with at the Simon Initiative.

As long as people have been innovating there have been people who can’t see how change is even possible. But change is inevitable. I think that it’s up to us to shape the ways that our societies change so that it can be as good as possible for all of the people (and not just some of the people) in our global communities. Grappling with change is an incredible challenge, but also a fundamental part of what it means to be human.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.