The art of teaching is naturally an iterative process. Even without formal reviews or reflection, the things we learn as educators while in the act of teaching often stick with us subconsciously for the next time we teach. The self-awareness of what works in the classroom, and what doesn’t, is partly what makes a great educator. But that self-awareness can be hard to develop. I’ve always found some kind of formal review or reflection is always useful in assessing what I’ve done previously, where I’m at now, and what I want to do, in both the short term and long term.

The Art of Teaching

There are many facets of teaching one could potentially reflect upon, but as I find a new semester approaching, I prepare for an upcoming course by revisiting the last iteration of it that I taught. Obvious things, like updating the syllabus, are good opportunities to think about the pacing or sequence of the course content. I might consider adding or removing a midterm exam, or changing the type of homework assignments.

For me, justification for changing these structural elements of a course can be based upon my own reflection of the last time I taught the course and recognizing something didn’t work. Or it can be as simple as wanting to try something new. If the change doesn’t work, I know I can always change it back the next time, and I will still probably learn something from the experience. My constant tweaking of course elements, no matter how small, makes the teaching experience more interesting and fresh. I think it’s important to remember that even if you’ve taught the same class ten times, the next group of students you teach will be taking that class for the first time. Changing things up helps us get off of autopilot and become more engaged as educators.

Another process I’ve started to use recently is to review student comprehension of course content. Gauging student understanding can be achieved in various ways that provides a multitude of feedback, but I primarily focus on the final cumulative exam. I like to use the final exam as it provides the widest scope possible in terms of course content. This means, outcomes of any review can be applied to the whole course. It also is one self-contained piece of assessment and reflection that I can reasonably manage in terms of workload.

Reflecting on the answers AND the questions

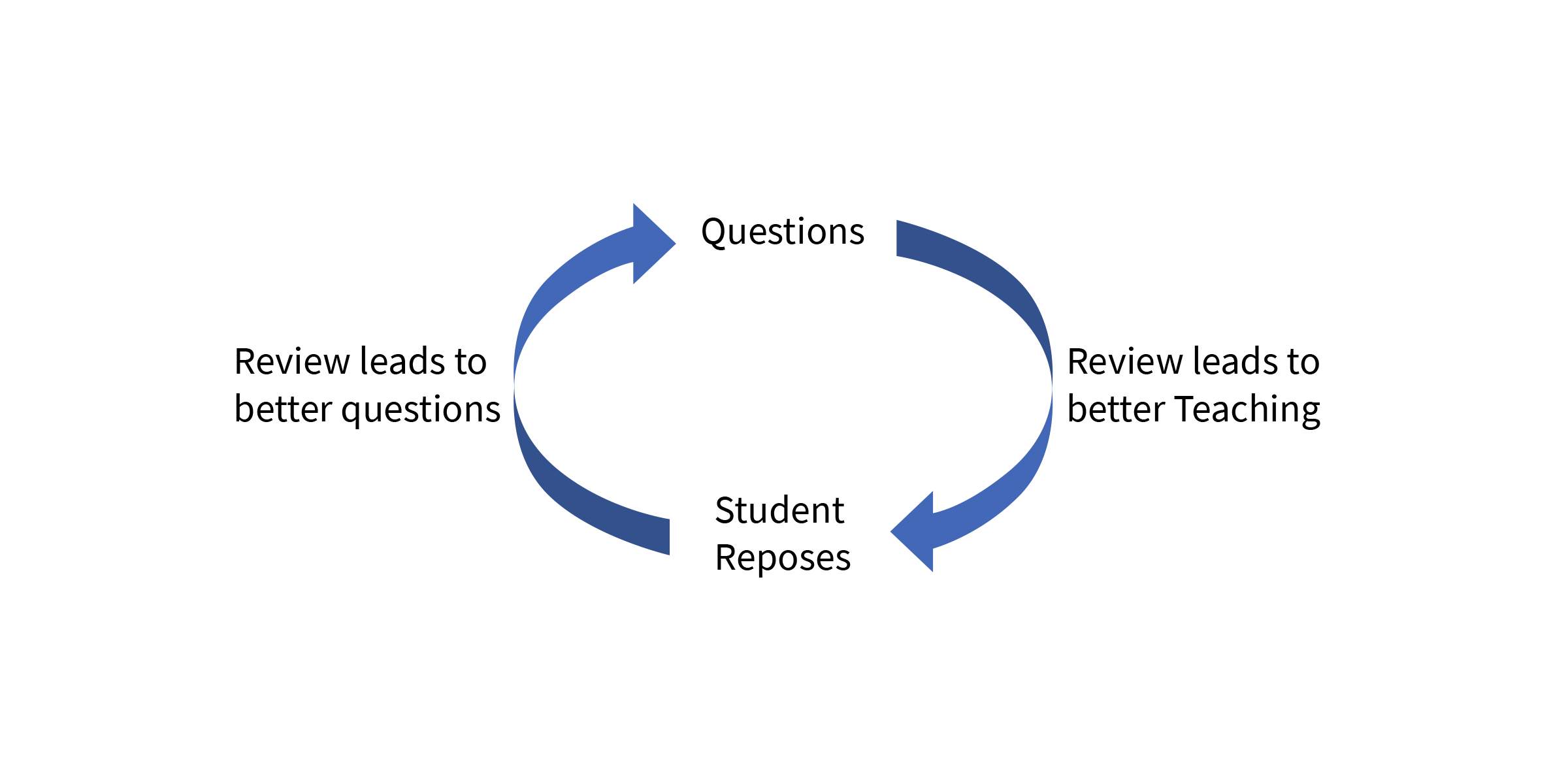

Unfortunately, gauging student comprehension from an exam is not without problems. I commonly encounter students who are initially unsure of how to answer a question when asked in a certain way, but can solve the problem when the question is rephrased or presented in a different manner. Consequently, while I could use poor performing questions as an indicator of an area of the course that I need to teach better, I also cannot discount that perhaps the way I worded my question made it more difficult than it needed to be. Recognizing that student performance on exam questions is inextricably linked to the quality/type of question, and not just student comprehension, allows an instructor to not only try to improve their teaching, but also try to write better questions.

In reviewing the student responses on an exam I hone in on the questions that were done really well or really poorly. For the questions done well I critique the question. Was it too simple? Or too close to class/homework examples? Did it not test a student’s deeper critical thinking skills? I’ll make a note of these questions in a review document so that when it comes time to write the next exam I have the information readily available.

When re-writing the question, it’s best to wipe the slate clean and start from new rather than making minor adjustments. A completely different approach to creating the question will better test if students are really understanding the content. I’ll likely throw in a curveball or add a part that requires a more advanced understanding. This will act to separate out the students of excellence from the crowd.

For questions done poorly I follow the same routine. If a piece of content is consistently not scoring well despite different question types, then it can inform my teaching. Perhaps I need to go slower or provide more examples of that content. Having that information available in my review document is critical at the beginning of the new semester as I start to plan. But if scores improve then I can try to determine why.

Perhaps my original question wasn’t clear? Maybe I originally expected too much from the students? Maybe I covered the content better this time? Either way, the process of trying to write better questions is tied into this loop of reflection and feedback with my effort to be a better teacher. Much time is often given in pursuit of becoming a more effective and engaging teacher. But if exams are how we primarily assess our students, then one should also not overlook the importance of becoming a better question writer.