“If there is a special place in Hell reserved for professors, it is to be seated in a large auditorium forced to listen to lectures for all eternity.” — remarks overheard at a professional development workshop for teachers.

If you are a new educator, and your assignment is a “lecture” course, you have a problem: student experience in lecture halls tends to be passive, disengaging and often dull. To succeed, any lecture needs to encourage active learning, student engagement and interest.

The easiest thing, of course, is to “teach as we were taught”… a content-rich monologue on the topic of the day. But most of us have sat through enough of these lectures as students ourselves to think “there has to be a better way”.

Here are some small steps you can take in the quest for more successful lectures. As with any heroic quest, the more steps we complete, the closer we are to reaching the goal.

Need a hand putting together your class? Take a look at our Top Hat Teaching Tool Kit — it’s free, and features a lecture plan, assessment guides, a lecture template and more.

Before your course begins

1. At the beginning, skip to the end

Identify the main issues you wish students to understand by the end of the course. Design backwards — start with the goal(s) you wish to achieve, then build the classroom experience as a pathway to help students get there.1

2. Who cares… and why?

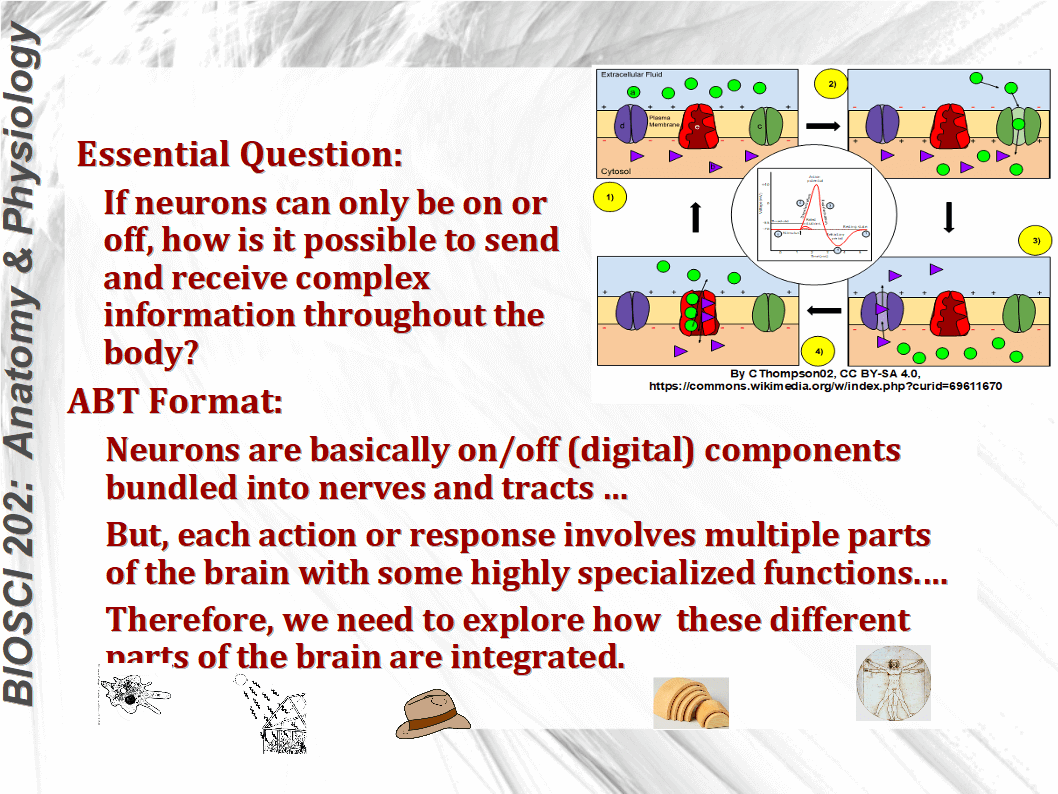

What are the “essential questions” of your field… the big, important issues that researchers study2? And what is the benefit of knowing the answers? Connecting your course to the world outside the lecture hall will anchor it for your class.

3. How will you know when you succeed?

What will your students do to demonstrate that they have learned the material successfully? As a part of the backward design strategy, lectures are built around the plans to assess your students’ success.

4. A picture is worth 10,000 words

Find or create strong visual representations for your lectures. Publishers often provide illustrations to instructors, but you can also find materials to use under Creative Commons licensing here.

5. Learn your lines

Although a “lecture” is etymologically a “reading,” think of your role in the class as the narrator, connecting a sequence of questions, ideas, concepts, and supporting visuals to tell the story. Practice speaking from notes, instead of reading from a text.

6. Plan for student responses

However you engage student responses in class, plan the questions you will ask, the answers you will accept, and how you will respond to students’ questions. Don’t forget to include those three words that professors find so difficult to say: “I don’t know!”.

During the lecture

7. Get to class early

At least on the first day, test the media, lighting and general features of the room; leave enough time to call for help (and bring extra batteries, markers or other expendables).

8. Tell them why they’re there

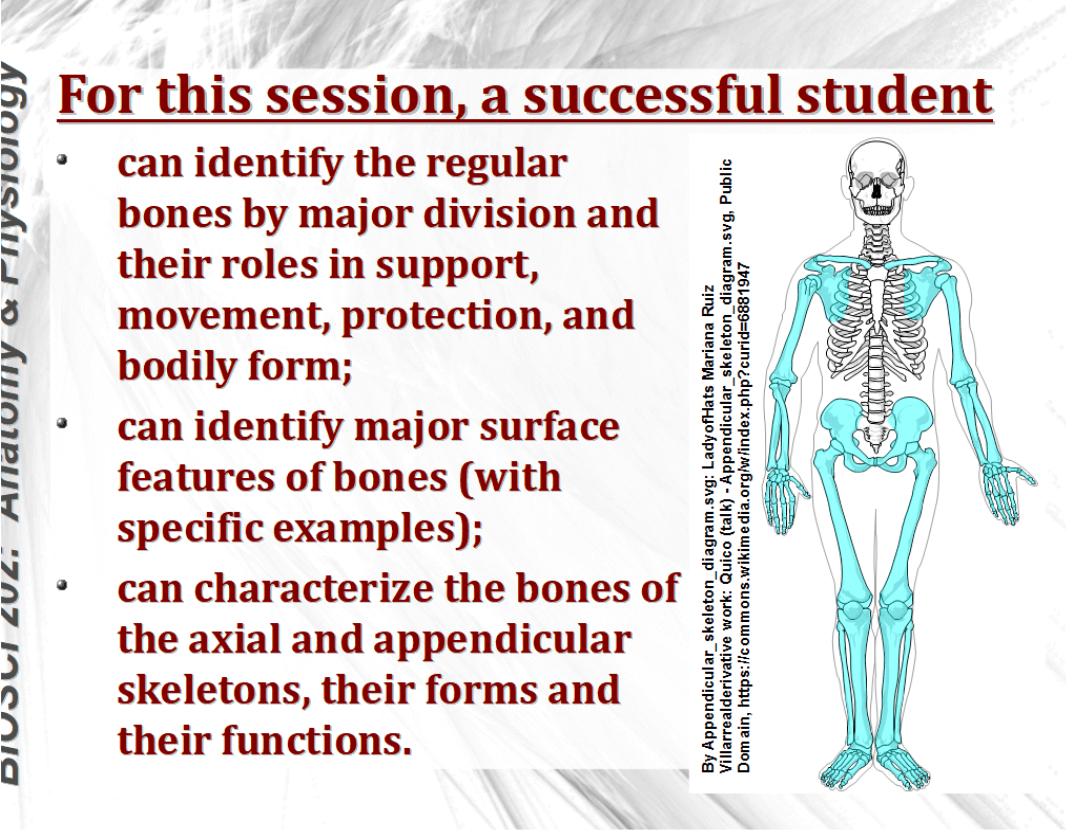

Be sure to list the learning objectives for the lesson or unit at the beginning, and summarize them at the end of the presentation. (Example below.)

9. Be the narrator

Tell the backstory to your students: the people, places, and problems that led to these great discoveries that changed how we know what we know.

10. “I’ll take theory for $200, Alex”

Remember that whatever text you have chosen is full of answers; but the questions themselves are often more interesting.

11. Engage

For you, make eye contact with students and scan the room as you talk; for them, make them stop and think by giving them problems to solve or questions to answer.

12. Connect

Use metaphors or guided inquiry to help students connect new information with existing knowledge.

13. Challenge

Ask deeper questions: “Why is this the correct answer?” or “What does this tell us about the next thing we need to learn?”

14. What should students remember to tell their grandchildren?

Avoid trivial details, but focus on “uncoverage”—relating the day’s content to the underlying themes and issues of the field. (Uncoverage aims to help students see what ideas, questions, arguments and applications connect and make meaningful the array of facts that may seem unrelated to them without the instructor’s guidance; p99, 1011).

15. Observe and respond

Pay attention to facial expressions, body language, and student behaviors among the students in your lecture hall. If people aren’t connecting with your topic, change gears.

16. Get immediate feedback

At the end of lecture, ask students to tell you what they understand or don’t, what confuses or concerns them or what needs more explanation. Then use this information for the next lecture, if you cannot address it immediately.

After the lecture is over

17. Assess and review

Use video or a helpful colleague to help you review your lectures. Even veteran lecturers can benefit from an independent observer.

18. Self-reflection

Be honest with yourself about how closely the experience resembled your expectations for the lecture. If it didn’t, think about how to improve the match.

19. Review student progress

Gather the evidence you took during and after each class about how well students are meeting the objectives you have set for the lesson. This can include electronic polls, or other techniques to help you determine if students knew more (or knew it better) after the lecture than before.

These are just some suggestions on how to enhance the main purpose of our lectures: to improve student understanding of our course materials. Commitment to this fundamental goal and our reflection on how well our lectures succeed are the essential ingredients in the recipe for success. As with any recipe, it may take some practice to get it right, and there is always room for experimentation and customization. The goal is to find the style and practice that are most successful for you.

Our Teaching Tool Kit is a free library downloadable online teaching tools, produced in collaboration with educators. Get guidance and examples with Bloom’s Taxonomy in teaching, activity planning, active learning, and more. (And we’re always adding new tools, too.)

Reference

- Wiggins G, McTighe W. 2006. Understanding by Design, Expanded 2nd ed. Alexandria (VA): ASCD.

- Elder L, Paul R. 2005. The Miniature Guide to Asking Essential Questions. Tomales (CA): Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Related pages

Learn how to increase student success in the online classroom using Top Hat