Institutions are struggling to adapt to today’s diverse student body: according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, Hispanic and black students’ graduation rates in 2018 were only 48.6 percent and 39.5 percent, compared with Asian and white students (68.9 percent and 66.1 percent, respectively).1

The push for understanding what is inclusive education at colleges and universities has only started happening recently, as more robust data on student achievement is becoming available. And the first thing that inclusive teaching addresses is the fact that traditional teaching methods have not served every student well, particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. With students balancing professional, personal, social and academic concerns, instructors need to be mindful of how they can create a safe and inclusive space where all students can thrive.

Kelly Hogan and Viji Sathy, two STEM professors who lead innovative classroom and diversity administrative initiatives at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and offer workshops on inclusive teaching, have noticed the shift. “National conversations on just about any topic have focused on inclusion in ways we’ve never seen before,” the pair told Top Hat by email. “Our students are a part of these conversations and they are learning how to articulate discomfort and ask for what they need.” However, online and blended learning environments raise some new challenges for instructors: How will you get to know your students? How will you gauge where they are struggling? How will you assess if they are engaged in course material? Here are 20 ways to do just that.

Table of Contents

- What is inclusive education?

- What educators can do to improve inclusivity

- 20 strategies to make your teaching more inclusive

- Introductions and level-setting

- Assignments and expectations

- Building an inclusive community in the classroom

- References

What is inclusive education?

Inclusivity in the classroom is best described as a “mindset” that embraces a student-centered approach to teaching, rather than a reactive, teacher-centered approach.1 Inclusive education means that all students attend and are welcomed by their institutions and are supported to learn, contribute and participate in all aspects of the classroom community. Inclusive education is also about how administrators and educators design and develop institutions, courses and degree programs so that all students are able to learn and engage together in ways that effectively meet their diverse needs.

For John Redden, Associate Professor of Physiology and Neurobiology at the University of Connecticut, promoting inclusivity in the classroom means that if he’s in his comfort zone, it “doesn’t necessarily mean that’s what’s best for my class or that my students are comfortable.”

Redden takes a broad view when talking about inclusivity: “It applies to LGBT groups, students of color, disabled students, first-generation students, and in many cases, we can include women.” In practice, say Hogan and Sathy, “it means not blaming students for differences and planning course designs and classroom facilitation that are structured to work for more students… Imagine a core group of students that seem highly engaged in class discussions and a handful that rarely get engaged. Rather than blaming some students for behaving differently than others, we need to reflect on different methods we can use to ensure all perspectives are part of a conversation.”

What educators can do to improve inclusivity

When it comes to closing the gap in college completion rates, Hogan and Sathy believe professors need to place student success at the center of their efforts, because the classroom is where many student difficulties originate. Whatever your starting point is, increased awareness of inclusive teaching is relevant in every discipline: “We have seen students grow in their confidence, performance, interest in our disciplines, ownership of their learning, and overall success.”

However, online and blended learning environments raise some new challenges for instructors: How will you get to know your students? How will you gauge where they are struggling? How will you assess if they are engaged in course material? Here are 20 ways to do just that.

What is culturally responsive teaching, and why is it important?

Culturally responsive teaching, or culturally relevant teaching, allows educators to celebrate and acknowledge the cultural backgrounds of all students. This form of teaching lets educators—in both K-12 public schools and higher education—create curricula that validate and highlight a wide range of identities, ethnicities and cultures. Culturally relevant pedagogy was first introduced by Gloria Ladson-Billings, Distinguished Professor of Urban Education at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. She called for a new form of diverse teaching that would engage and celebrate students’ cultures that are traditionally left out of higher education.

From a neuroscience perspective, culturally responsive pedagogy forms the foundation for student success. For instance, the human brain is wired to make connections. Students bring their background knowledge to the virtual classroom. Culturally responsive teaching allows them to make connections between their ‘old’ knowledge and their ‘new’ knowledge. Professors are able to maximize academic achievement by embracing the unique backgrounds of students. Educators can cultivate a sense of belonging by representing all cultures and backgrounds in their class. A student who sees their ethnicity represented in course readings, case studies and other instructional design elements is likely to feel empowered and seen.

20 strategies to make your teaching more inclusive

Introductions and level-setting

1. Get to know your students

Asking students which pronouns they prefer is a meaningful way to establish an LGBTQ+-friendly classroom, says Redden: “I start my classes every semester by saying, ‘I’m John Redden, I’m an associate professor, my pronouns are he/him/his.’ I also include gender pronouns in my email signature.”

“You just kind of establish it as the norm from the get-go, and that makes it easier for other students to volunteer their pronouns if they’re comfortable. I think that’s a really easy thing to potentially do.” Acknowledging and accepting differences between students is an important part of creating an inclusive classroom.

We should ask ourselves often: for every choice that we make in our course design and environment, who might be excluded as a result of this practice?

A common mistake Hogan and Sathy see is faculty who come in expecting to teach the way they were taught: “It’s difficult to see other perspectives without some effort, so we recommend that faculty learn more about their students’ lived experiences in one-on-one settings, through surveys, and asking them about what makes them feel excluded/included in a classroom.”

2. Monitor your interactions with students

If you are recording your in-person or synchronous online class sessions, try re-watching the lecture videos and taking notes on student interactions, the types of examples you use and the clarity of your explanations. Consider asking yourself what trends or specific actions stand out, and the impact they might have on your students.

As an instructor, it’s important to recognize your own implicit biases. Implicit biases are unconscious attitudes that we hold towards groups of people—or the stereotypes that we associate with them without realizing. Everyone holds implicit biases. Recognize your own by taking a test offered by Project Implicit, an initiative from Harvard University. Being aware of your biases can help you act as a better support system for your diverse group of learners.

3. Learn your students’ names

Calling students by name helps them feel recognized as individuals and can make shy students more apt to participate. This goes for in-class activities as well as discussion threads. If you have a large online class, consult the online roster for your course. Demonstrate caring by directly asking students to learn about pronunciation or any preferred names they would like to be called.

4. Reflect on your students’ identities

Examine the contexts and conditions in which students may find themselves while taking your course. Reevaluate the assumption that all students are in a space that provides them with a productive learning environment. Consider using a student interest inventory to learn more about your students. Use this as an opportunity to ask about their work and family responsibilities, current course load and past academic experiences. This provides insights for you to better understand how to best help your students succeed, and helps keep tabs on student mental health as well.

Online courses in particular can highlight student inequities. Not everyone has the basic means of connecting to virtual classes. Students will benefit from a safe space dedicated to sharing their learning styles, lives outside of the classroom, barriers to learning and academic priorities. A student interest inventory, a form dedicated to gathering personal and academic information, can help you design your curriculum accordingly.

5. Check your assumptions

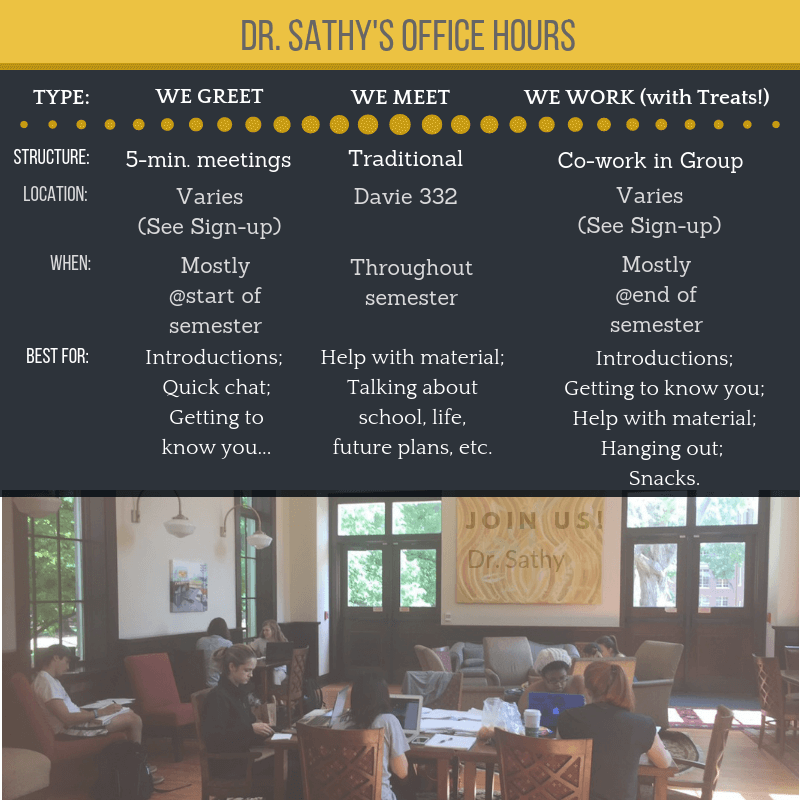

Academics are now openly discussing the fact that less privileged students have a difficult time making sense of their college experience, what many refer to as the “hidden curriculum” of higher education. Office hours are a perfect example, say Hogan and Sathy: “We often tell students when they are, but we don’t tell them what they are and how they can be used (see Harvard professor Anthony Abraham Jack’s new book The Privileged Poor). By providing more information [below], we are enabling all students to see the utility in meeting and not leave it to chance that some will know to use them and others won’t.” This is an easy-to-implement example of inclusivity in the classroom.

Redden also had to re-examine his own assumptions regarding the “hidden curriculum” and the challenges these create for disadvantaged students in order to ensure he was prioritizing inclusion in the classroom: “There are students that don’t know what office hours are. Students can think office hours are the time when I’m in my office and don’t want to be bothered because I’m working on a research project or something like that. But sometimes students don’t know really basic things like that. It is so implicitly built into the core of every class that we do as instructors. It assumes that students have some kind of mentor or a parent or a sibling or a friend that can help them navigate through those situations.”

Assignments and expectations

6. Overcommunicate your expectations

Communicate clearly—from the first day of class—about what you expect to happen in the classroom, including your expectations for respectful and inclusive classroom interactions.

7. Ask for feedback

Try asking a trusted colleague or mentor to observe your online course or view one of your recorded lecture sessions and provide their comments. Online polling features are a great way to quickly assess student understanding of course material and to collect ideas to improve the learning experience for everyone.

8. Share what you’re doing with the feedback

When you collect feedback, be sure to take time in class to explain how you are integrating their suggestions. What concerns are you prioritizing? What changes or adjustments will you be making? Showing you take feedback seriously will help strengthen feedback loops by making it more likely for students to contribute in the future.

Ideas for effective teaching methods don’t always have to stem from teachers. Students who take an active part in their own learning have a much more empowering learning experience. In an academic context, students who teach a subject to their peers are more likely to better comprehend the material by way of problem solving in groups. In a non-academic context, student-student learning can help create the essential peer connections and interactions that have been strained with online learning. Peer-peer learning is also a way for students to infuse their own cultural knowledge into the classroom environment. Small group activities and even flipped classroom models can be employed to foster collaborative learning environments.

9. Be explicit with assignment instructions

Take time to provide clarity about assignment instructions. Being open about how and when they should be submitted and what resources are available helps ensure the work can be completed successfully. Walking them through an example can really help bring this to life. You can also share rubrics with students to ensure the grading process is transparent.

It’s also important for instructors to remember to set goals for each assessment. At the start of a learning activity, set objectives for real-time or self-paced interaction. For example, you could clearly outline how many times students should share responses in an online discussion board. Doing so will help you gauge learner progress and understand what recurring activities are working and which aren’t.

10. Share resources with the whole class

Ensure that assistance provided outside of class is equally available and accessible to everyone. For example, if you share information with one or a few students regarding how best to approach an assignment, repeat this information to the entire class. This ensures there is class inclusion and equity, as opposed to giving a small group of students an advantage. This also applies to student mental health resources. Those who are new to campus may not know about the services and opportunities available to them. Sharing them through an announcement on your LMS makes it easy for students to access.

Building inclusion in the classroom: examples

11. Foster a growth mindset

The foundation of a “growth mindset” is the belief that intelligence is not fixed or the product of natural ability, but can change and grow over time. When talking with students about their performance in class or on assignments, avoid describing such performance as a sign of natural ability (or lack of ability). Instead, consider working with them to develop two to three strategies they can use in areas where they are struggling. This is a key example of inclusion in the classroom as it encourages all students, regardless of their skill levels and abilities, to reach personal and academic goals.

12. Implement Universal Design for Learning

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework that guides the design of courses to benefit everyone involved in learning interactions. One low-stakes example of UDL is to require faculty to use microphones to build equity inside the classroom for students with disabilities. Overlooking this is one of the most common mistakes John Redden sees professors making. “A lot of times we have tech issues with the microphone or someone doesn’t like to use a mic so they’ll say ‘Oh it’s no problem, right? I’ll just talk louder.’ But in fact, that’s actually a noninclusive practice because you have students who might have a hearing disability or students with devices that integrate with the classroom sound system.”

Inclusive design can be as simple as a font choice, says Redden. “I make sure that I’m using a font that actually can be scaled up and isn’t some weird handwritten font. I don’t show graphs that are only red, green and black because that might mess with someone who is colorblind. There are lots of little things in terms of how we actually present information in the class that are not a lot of work but can make a big difference for someone’s experience in the course.”

13. Create community agreements

This can be done in a shared document or a discussion thread where students provide their own perspectives on online etiquette, norms and expectations. Students can also be charged with doing their part to establish and maintain an inclusive and supportive online learning community. This is always more effective if they’ve had a hand in building the community agreement themselves.

In the same way that you have distinct preferences for how you communicate, so do your students. Be flexible. For those less inclined to speak up in front of classmates, a discussion thread is a great alternative. Also, consider relaxing the rules around grammar and punctuation for online discussions. For many, using video, memes and GIFs are valid forms of communication in their personal lives. If the goal is active participation, broadening what is permitted will help get more students engaged in learning activities.

14. Set the ground rules

Develop and enforce a set of ground rules for respectful interaction in the classroom. These can include guidelines for contributing ideas and questions and for responding respectfully to the ideas and questions of others. If a student’s conduct could be silencing or denigrating to others (intentionally or not), remind the entire class of the ground rules. You can then speak with the student individually outside of class about the potential effects of their conduct. This way, you can ensure you are prioritizing diversity, equity and belonging on college campuses.

15. Create a sense of belonging

Diversity in the classroom can be fostered within course design and the class climate perspective. Redden always looks closely at his course content for the absence of relevant perspectives. “If I’m looking for a picture of a person, am I going to pick a white person or am I going to take someone from some underrepresented background? Everybody knows if you just do a Google search for scientists that you can find old white guys in lab coats. It might be better to put more diverse images out there into the world to try to let people see themselves in that position.”

Hogan and Kelly caution faculty to not just focus on diversifying the content of their classes, but also being more representative of different people and ideas. “Focus on making more students feel included in conversations, reading, taking notes and collaborating. We have both found that the act of telling all students ‘you belong here’ after a first exam and at other points in the semester is really powerful for students, particularly those who are doubting their abilities or feeling impostor syndrome.”

16. Mistakes or learning moments?

Create an environment in the classroom or laboratory in which it is okay to make mistakes. Faltering, after all, often leads to deeper, more meaningful learning. If a student contributes an answer that is incorrect, ask questions to help the student identify how they arrived at that answer. This can also help the class as a whole understand alternative ways of reaching the correct answer. And be sure to thank the student for having the courage to share with the rest of the class.

17. Diversify your syllabus and course materials

If you assign text or media that may be problematic or incorporate stereotypes, identify the shortcomings and consider supplementing them with other materials. Encourage your students to think critically about course materials and potential biases to strengthen their analytical skills.

18. Approach sensitive topics proactively

If you are teaching topics that are likely to generate disagreement or controversy, identify clear objectives and design a class structure informed by those objectives. Communicate the objectives and the conversation’s structure to your students, so that they know what to expect.

19. Allow for anonymity

You can also choose to make discussion threads anonymous to ensure all students feel comfortable voicing their opinions navigating sensitive topics in the classroom. But be sure to remind your classroom that the rules of decorum and netiquette still apply.

20. Be a positive example for open dialogue

Model openness to the new ideas and questions your students bring into the course. This can broaden and deepen your own knowledge of your discipline and its relevance. Help students understand that knowledge is often produced through conversation and collaboration and by exploring disparate points of view.

References

- Completing College – National – 2018. (2019, May 15). Retrieved from https://nscresearchcenter.org/signaturereport16/

- Introduction to Inclusive Teaching Practices. (2013, October 30). [White paper] Retrieved from https://www.uottawa.ca/respect/sites/www.uottawa.ca.respect/files/accessibility-inclusion-guide-2013-10-30.pdf