Some professors may put race and politics at the forefront of class discussions. Others may tiptoe around these issues in their lessons. The bigger question: how do you ensure your students are equipped to engage in respectful and empathetic civil discourse? How do you even begin to respond to accusations of racism in your course?

Microaggressions are best described as intentional—and unintentional—verbal or non-verbal remarks that come across as hostile or derogatory to a target group based on their race, gender, sexuality, or other intrinsic trait.1 Political polarization and correctness may cause many to feel uncomfortable engaging in healthy, two-way dialogue. But that shouldn’t become the status quo. We’ve rounded up frameworks and tips from your peers on how they tackle sensitive topics in class. Plus, we share some simple ways to promote micro-affirmations—messages of excellence, opportunity and empathy—towards your next group of students.

How to reduce the likelihood of microaggressions in the classroom

1. Trust-building is the first step to having productive conversations

Forming camaraderie, connection and trust with peers can be a challenge for students. Dedicate the first one-to-two weeks for rapport- and community-building among students before diving into racial- and political-focused conversations. Here are three ways to get started.

I. Allow for peer-to-peer learning

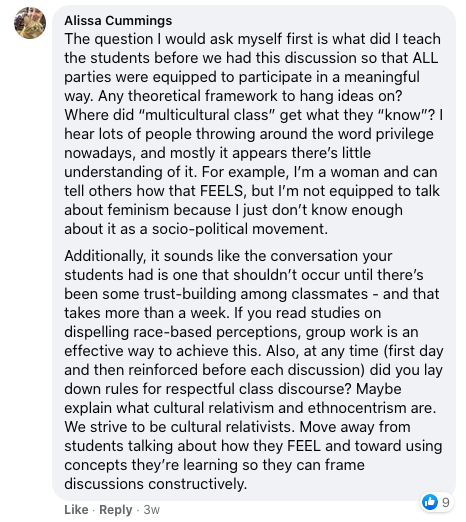

Alissa Cummings, Director of Career & Transitional Services at Niagara County Community College, suggests using group work and collaboration early on as a way to dispel race-based perceptions. The more frequently students become acquainted with one another, the more likely they are exposed to diverse points of view.

II. Set engagement ground rules early on

Respectful discourse starts with framing discussions constructively. Cummings argues that it’s best for students to frame their arguments around the course. “Move away from students talking about how they FEEL and toward using concepts they’re learning so they can frame discussions constructively,” she says. This has the added benefit of strengthening their argument—and can show they’re listening in class.

Setting the stage for your conversation is one of the most effective ways to manage difficult class debates. Kristina Ruiz-Mesa and Melissa Broeckelman-Post, authors of Top Hat’s Inclusive Public Speaking title, always set parameters for their discussions to help students understand all sides of a topic. For both professors, this means setting rules such as ‘listen carefully’ and ‘avoid inflammatory language’ to reduce the chance of microaggressions in the classroom from occurring. “It’s not about avoiding dialogue, it’s about doing so in a way that doesn’t damage people’s experiences with their learning and allows them the opportunity to continue to learn in this course,” Ruiz-Mesa shares.

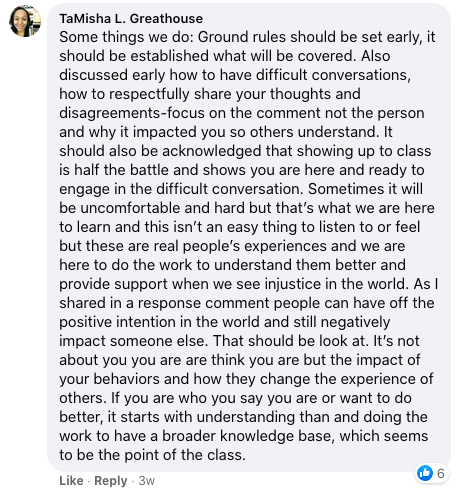

III. ‘Focus on the comment, not the person’

Political or racial conversations can quickly take a turn when ideas and course themes are overlooked—and when personality and attitude take center stage. Be sure to share a respectful framework on how students might respond to one another in moments of tension, so says TaMisha Greathouse, UCLA resident director. “Discuss early how to have difficult conversations, how to respectfully share your thoughts and disagreements—focus on the comment, not the person—and why it impacted you so others understand,” she writes.

2. Ensure you address any incidents in front of your class

The goal of productive class discussions is to focus on ideas—not their originators. Yet this may be easier said than done with racially- or politically-charged statements. It can be troubling to spot microaggressions in the classroom. Implicit biases, in turn, also determine how we view certain statements.

Viji Sathy, a professor in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, emphasizes the importance of addressing microaggressions in class—even if it means taking some time to develop an approach. “If you’re feeling unsure about how to address it specifically in the moment, it’s ok to give yourself some time to determine the best course of action. Just say, ‘I’m going to make sure we come back to this and we’ll bring this up in the next class session.’ What this communicates to students is, ‘wait, something just happened.’ Because if they didn’t recognize it as a microaggression, now all of a sudden they’re attuned to something happening,” Sathy recommends.

A more robust framework like RAVEN can help you constructively address the incident that occured. This model was proposed by Dr. Luke Wood, Vice President for Student Affairs and Campus Diversity and Distinguished Professor of Education at San Diego State University and Dr. Frank Harris III, Professor of Postsecondary Education and Co-Director of the Community College Equity Assessment Lab (CCEAL) at San Diego State University.2 Below are five steps you can take to address microaggressions in the classroom should they occur.

- Redirect the interaction. Stop the conversation to prevent further harm to the students who are present.

- Ask probing questions. They can create cognitive dissonance and help the student recognize that their statement is problematic.

- Values. Clarify which values your classroom operates around such as trust, diversity, inclusion and treating everyone with respect and dignity.

- Emphasize your own thoughts and feelings through “I” statements, followed by an explanation of how the student’s words or actions may have impacted another learner.

- Next steps involve suggesting what the student can do to correct or change their behavior in future classes.

3. Summarize the discussion and allow for student reflection

A lot can unfold when discussing microaggressions in the classroom. As an educator, ensure you adequately summarize the conversation and be clear in your approach when addressing the incident. Students may understandably be overwhelmed. Having an open discussion, as Suzanne Buglione, Vice President of Academic Affairs of Bristol Community College, writes, can make students feel part of a connected community. It also shows your empathy and diligence in resolving the matter. “I’d consider having a debrief asking students what happened (just the facts) and then how people felt,” she writes. “I’d follow that with some class agreements developed collectively to guide future discussions and challenge all to hold each other accountable to them.”

Allow students to reflect on their peers’ remarks and the discussions that unraveled as a result. Consider that not all students will want to share their feedback live in front of everyone. Alicia Moore, Associate Professor of Education at Southwestern University and Molly Deshaies, Elementary Education major at Southwestern University, suggest writing as an effective medium, which will allow all students to feel comfortable expressing their thoughts in a more controlled environment.3

Encourage students to share their responses privately with you via email or your learning management system (LMS). Prompt students with new opportunities for discussion, awareness or reflection. Finally, use student responses to develop learning activities to help strengthen community and diversity in future classes. Doing so will help you be proactive in addressing microaggressions the next time they arise.

Using micro-affirmations to make every student feel seen and heard

Micro-affirmations are small and often covert acts, gestures and comments that demonstrate care and concern. Think of it as opening a door to opportunity and inclusion especially for students who may have previously felt socially or culturally excluded from your classroom. The end goal? All students should feel comfortable offering ideas and understand that they are valued and supported. Below, we share three key categories of micro-affirmations and some tangible practices that can help you embrace a more equity-minded role in your next class.

| Actively listen | Recognize and validate experiences | Affirm emotional reactions |

| Ask qualifying questions to make sure statements aren’t taken out of context | Make sure to call on students of different races and genders equally | Use empathetic statements such as “I appreciate that this is frustrating” or “I understand that you may be disappointed” |

| Ask students for their preferred names, pronouns and name pronunciations—which may be possible in your LMS | Use inclusive language such as “families” instead of “parents” or “folks” instead of “guys” | Mix praise of what’s working with constructive feedback on how to improve |

| Use open-ended discussion questions to allow for a variety of diverse viewpoints | Reward behaviors such as seeking extra help with statements like “I see you’re making great progress in this area, excellent work” | Remind students where and how they can reach you beyond class time should they need academic or non-academic support |

References

- Sue, D. (n.d.). Examples of Microaggressions in the Classroom. https://www.rit.edu/diversity/sites/rit.edu.diversity/files/2020-08/Microaggressions_in_the_Classroom.pdf

- Wood, J. & Harris III, F. (2020, May 5). How to Respond to Racial Microaggressions When They Occur. https://diverseeducation.com/article/176397/?fbclid=IwAR0WY_Hmlal36-BMgy1LrO2Kcl6sImm4fWQM5zoCGG7Nry_nfAa9jZ-iQTk

- Moore, A., & Deshaies, M. (2012). Ten Tips for Facilitating Classroom Discussions on Sensitive Topics. https://bento.cdn.pbs.org/hostedbento-prod/filer_public/SBAN/Images/Classrooms/Ten%20Tips%20for%20Facilitating%20Classroom%20Discussions%20on%20Sensitive%20Topics_Final.pdf