Top Hat is the active learning platform that makes it easy for professors to engage students and build comprehension before, during and after class. This interview is part of our recurring series “Academic Admissions” where we ask interesting people to tell us about the transformative role education has played in their lives.

Gina Cody left Iran in 1979, at the height of the Revolution. With a bachelor’s degree in hand, she landed in Montreal with $2,000 and a dream: She wanted to complete her master’s degree in engineering and start a new life in Canada.

After a fortuitous meeting with a professor at Concordia University, that dream started to become reality. In 1981 she got her master’s. In 1989, she became the first woman in Concordia University’s history to earn a PhD in building engineering. In 2018, after a decades-long career in which she rose through the ranks of a high-profile engineering firm, she donated $15 million (CAD) to Concordia’s Faculty of Engineering and Computer Science. That gesture led to Cody becoming the first woman to have an engineering school named after her in Canada, an honor that she doesn’t take lightly.

“Higher education is important for women, and the renaming of the faculty, it wasn’t really for me.” For many years, says Cody, female engineers felt like they were second class citizens. “Now, they’re accepted.”

I was brought up in Iran, in a family where education was extremely important. My father ran an all-boys private high school. He was a teacher, and he strongly believed in women’s education—mainly higher education—and of women being equal to men.

I came from a family of five—three boys and two girls. My brothers became engineers; my sister is a dentist. I was the youngest. As a child, I was always driven to do things. I wanted to fix things. If the TV was broken, I’d get the bulb out and go to the store and find a new bulb to fix it myself.

My mother always used to say to me and my sister, “I really don’t care what happens to the boys. You two girls, you’d better go to higher education because that is only way you can be independent.” She believed if you didn’t go to university, you’d end up dependent on your male counterpart. And that independence also has to come with respect, because it’s not just monetary—it’s the respect you gain from the society as a person. She believed that higher education would give you the respect that you deserve.

Getting into higher education was a mandate given to me and my sister both. In the 1970’s, I went to Aryamehr University of Technology (now Sharif University of Technology) in Tehran and completed my undergraduate engineering degree.

When I was in the first year of university—I got to university at age 16—my Dad had me work in his high school in the summer to teach courses in physics, math and algebra. He would have me teaching boys who were 14 and 15—boys that were just a year younger than me. That made me be very comfortable among men. I never felt I was different.

What was always different was in university: It would be four or five men to only one woman in some classes. Because of that, I always wanted to do my best.

During my undergraduate course, we were being taught by Iranians who had graduated from MIT. Once we had a physics quiz and everybody but one of us failed. The only identifier on our test was our student number. When the professor called my number, I had to show him my I.D. to prove that the only person who passed the test was me. He said, “It can’t be yours.”

He didn’t believe a woman could be the only one in the class that got it right. He thought it was just a fluke. That’s always stayed with me: that if I had been a man, he would never have asked me three times, “Is it really you?”

It made me stronger and determined to prove myself more.

A pivotal life moment

After I finished my undergrad, a Bachelor of Science degree in structural engineering, I left Iran. It was 1979, during the Revolution. Things were not calm. It was really unsettled, and Iranians—because of the hostage crisis—were not very well-liked at the time.

I ended up in Montreal after being accepted at McGill University for a master’s program. I had only $2,000 (Canadian dollars) in my pocket. Tuition at the time was $4,000. My brother had just finished his engineering degree at Concordia. I arrived during the Labor Day long weekend, and school was starting that week. So my brother says, “Before going and registering at McGill, why don’t you come and see this Concordia professor I know?”

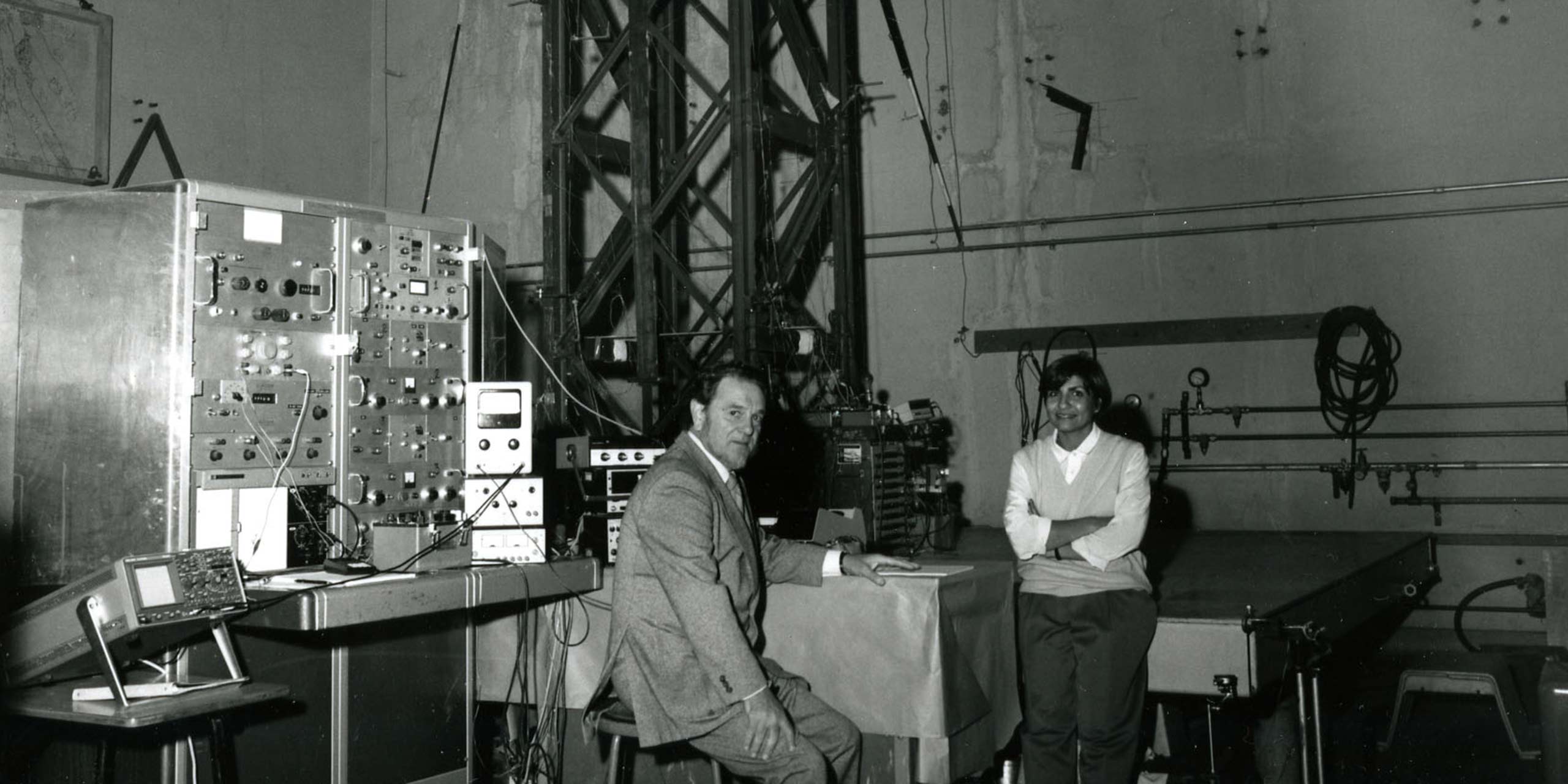

So I went and met him, engineering professor Cedric Marsh, and he looks at my marks. I had an interview with him, a long interview. He said, “I’m going to give you a scholarship. I have a lot of projects.” So he took me to the registrar at Concordia, because I didn’t have acceptance there. He says, “Here is her acceptance to the other school, and these are her marks. Give her an acceptance to Concordia.” And then he says, “I want her to start work this afternoon. She needs a work permit.”

I went to the Immigration Canada office and gave them the letter. They stamped it. I came back, and that afternoon I started working in the lab.

That’s where my story started. I took my courses and was starting a new life. I was so busy trying to prove that I really deserved the trust that was given to me. I worked very hard. I would stay till 11 or 12 o’clock every night in the lab, finishing up the tests and studying. In 1981, I got my master’s degree in engineering. I was young and at the time, I think I took it for granted. I just thought I was lucky. But when you get to the workforce and look back, you say, “Okay, what was the pivotal moment in my life?” I think it was that morning I met Cedric Marsh.

In 1986, three years before I finished my PhD, I came to Toronto because the job market there was more attractive than Montreal. I was offered a job at the Ontario Ministry of Housing writing the building code.

During that time, I was assigned to run a committee for the Ministry with the building industry and everybody who was in that committee—they were all consulting firms—wanted me to join their ranks. I felt I wanted to progress and do more things than just working on building code, so I accepted an engineering job at a company.

They had just bought a small company and they said, “You work here.” All of a sudden I was doing everything from washing dishes to doing engineering work at night because it was a very small satellite office.

The person who was running it was retiring. There were engineers with more knowledge and experience than me in that company, but I was more of a doer—I would come in at 6 a.m., prepare the coffee, then do all the drafting, put the whole organization in place and make sure that jobs were assigned properly. Then I would go and do those jobs and come back. They’d have more jobs, and I would say, “Don’t worry. I will do it. I’ll stay late and I will do it. Just let me know how it is done and I will do it.”

That’s how I got myself to be accepted in this field as a woman, and to me, it was natural. I didn’t do it because I was trying to force myself on them. It was just a natural thing. It has to be done. Who else is going to do it? Nobody else is doing it. I’m doing it because it just takes another half an hour. So what? I have the time. I can do it. That meant the work week was 80 hours, 90 hours, 95 hours. Didn’t matter.

I was young. I was energetic. I didn’t have kids. I had a husband who was extremely supportive, so if I had to work late at night, he didn’t mind. I’d bring work home Saturdays. I had to go to job sites on Saturday or Sunday. It didn’t matter.

Gradually, I became a partner of that firm and I bought out all its shares.

The ‘stamp of approval’

If I had to go to a meeting, I would memorize the agenda. If I had a report that I had to submit, I would read it three times because, to me, I felt that they expected me to be wrong. I wasn’t going to let them catch me, or think that I didn’t know the subject matter, because I had to prove myself. I had to be right. If you had to be right, you’d better be right because you can’t fluff it. You can’t hide mistakes in engineering.

This is what my advice to young girls is. Two plus two is four. It doesn’t matter what color of skin you have or what gender you are. Nobody can argue with you. It’s not something that can be argued or work against you.

I think if I didn’t have that education, if I didn’t have a PhD—if I wasn’t Dr. Cody—I wouldn’t have been accepted in my industry the way I was accepted. As a woman in a STEM field, you’re not accepted as you are unless you have a degree behind you that proves your ability because somebody else has already put a stamp of approval on you.

I had my own consulting firm, and many times my executive assistant would pass an important call to me and if the guy didn’t know who I was, the first thing he would say is, “Can I ask to speak to your boss?”

I’m like, “She just passed you to me. I am the boss.” Then after a minute I would say, “Look, I have a PhD in engineering. I know what I’m talking about. So you can discuss your issues with me and I’ll guide you where you need to go.”

As soon as I would say, “I have a PhD in engineering,” I would get the stamp of approval. Then they would listen.

For women, I think it’s become more important than ever to get a STEM education. Without it, I believe they’re going to fall further behind. The third revolution—the digitization of manufacturing—happened. People didn’t think it was going to happen, but it did. And now, the fourth revolution—the blurring of technology into every part of our lives—has already happened, whether everyone accepts it or not. Today, the mission of women and girls getting into sciences becomes more and more important.

My motivation to succeed came from that pivotal moment in my life: the day after I arrived in Canada and was given the opportunity to learn at Concordia. I knew that if I succeeded, I had an obligation, not a choice, to pave the road for those coming after. How that comes to fruition is different for different people. But I believe higher education is important for women, and the renaming of the faculty, it wasn’t really for me. I really don’t want it to be about me.

In September 2018, Cody made an historic $15 million (CAD) donation to Concordia and the Faculty of Engineering and Computer Science—the faculty has since been renamed the Gina Cody School of Engineering and Computer Science. It is the first university engineering faculty in Canada to be named after a woman.

[Naming the faculty] is a message I want to send. I told them, “I never want you to refer to the school as ‘Cody.’ It has to be ‘Gina’ because it’s about the gender. When you have a faculty of engineering and computer science named after a female, a graduate of this school who reached a point where she can do this, just imagine how you girls can do it. Don’t be fearful.”

It’s amazing the comments I receive from female engineers who have never been to Concordia but are working in the industry. I think it’s the best thing I have ever done in my life. They felt they were second-class citizens. Now, they’re accepted. That’s very important.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.