Top Hat is the active learning platform that makes it easy for professors to engage students and build comprehension before, during and after class. This interview is part of our recurring series “Academic Admissions” where we ask interesting people to tell us about the transformative role education has played in their lives.

Internationally known as an authority on creativity and innovation in education, Sir Ken Robinson is the first to admit he didn’t arrive fully formed. As he tells it, his ideas about education reform were shaped by his own history: Growing up with polio in working class Liverpool he knew he’d have to earn a living by using his head, not his hands, so he worked hard to differentiate himself academically.

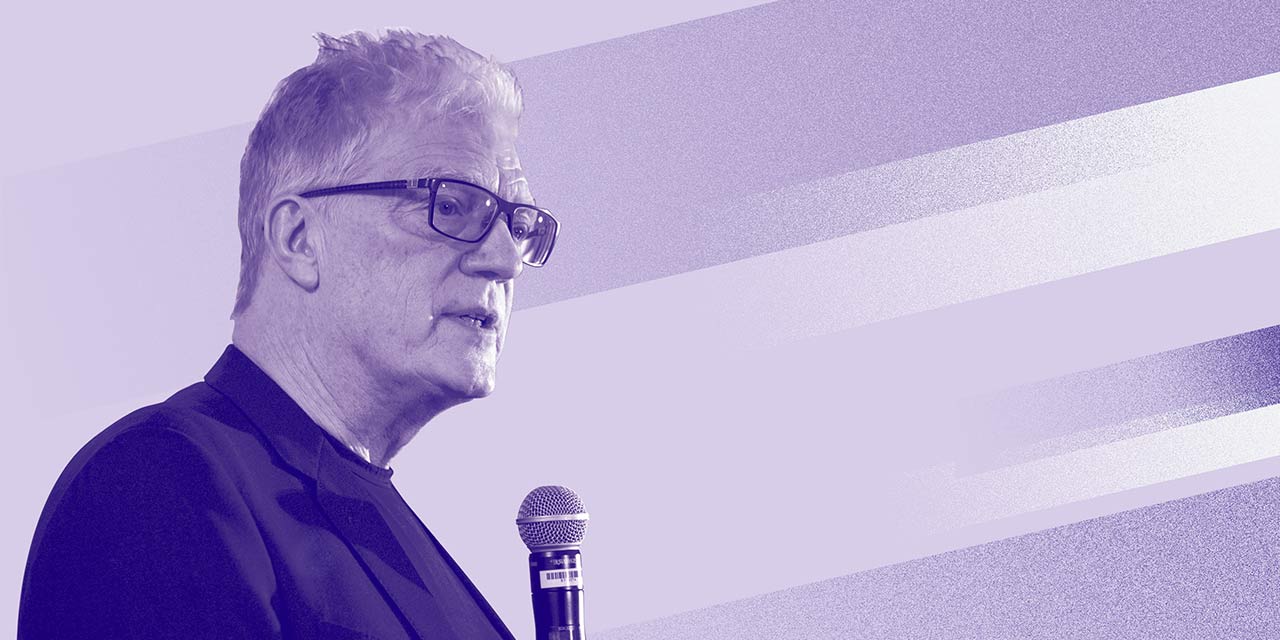

He took it upon himself to add culture to the grammar schools he attended and never ceased to be fascinated by the diversity and potential of the people around him. His passion for pursuing ideas that interest him has led Robinson from Liverpool to the international spotlight—the author of multiple bestselling books, including The Element and most recently, Creative Schools, he’s advised governments and cultural agencies on educational reform, delivered the most-watched TED Talk of all time and been knighted by Queen Elizabeth for his services to the arts.

Watch his Engage 2018 keynote here.

I was born in 1950 into a large working class family in Liverpool, England: the fifth of seven kids, six boys and one girl. We grew up right next door to Everton’s soccer ground in the heart of the city. My father used to be a semi-professional soccer player and when I was a child, because I was very fit and strong, he thought that I might become a footballer. When I was four, I got polio. I spent eight months in hospital and when I came out I was paralyzed in both legs, wore two braces and got around in a wheelchair. That pretty much ruled out the soccer career.

At five I was put into special education at the Margaret Beavan Open Air Day School for the Physically Handicapped—they weren’t quite so good at euphemisms in the 1950s. The other kids in the school had all kinds of physical disabilities—polio, cerebral palsy, hearing and sight impairments. You name it. As kids we didn’t pay attention to each other’s disabilities. Like any kids, we made friends with people we found interesting or funny.

When I was ten we had a visitor to our classroom. I found out later that he was Charles Strafford, Her Majesty’s Inspector of Schools for special education in Liverpool. He went on to become a great friend to my family and me. He talked to the teacher that day and then wandered round the room talking with various kids about what they were doing. He spoke to me for a while. A few days later, I was summoned to the head teacher’s office and was asked to complete various tests by another man, whom I assume was an educational psychologist of some sort. Subsequently I was moved up into a different class and into the hands of a wonderful teacher called Miss York.

She set about preparing me for the eleven-plus exam, a test that most children in the UK took those days to determine what sort of secondary school they went to. Those who passed went to the high-status grammar schools, which were very academic: those who failed went to “secondary modern” schools, which were more practically oriented. The eleven-plus was a big deal in the lives of children and families in England at the time. For weeks after I took the test, we anxiously watched the mailbox at home for the official results envelope. When it finally arrived to say I’d passed the test, there was wild jubilation. I was then out of special ed and into mainstream education.

I went to the Liverpool Collegiate, a very traditional grammar school, which occupied a grand, castellated Victorian building near the city center. Long before I went there we used to pass it on the bus and I’d been intrigued by the kids in somber uniforms and teachers in black gowns swirling in and out of this dark, forbidding building. I’ve written a lot about the shortcomings of an exclusively academic education. It’s not because I dislike it personally—I’ve always enjoyed academic work—but it doesn’t appeal to everybody and it’s based on a particular and limited view of intelligence.

At any rate, I went there and loved it. Various teachers deeply impressed me with their passion and expertise in their various disciplines. I loved the traditions and rituals of the place—the timeworn classrooms and desks, the staid morning assemblies in the Great Hall. Looking back there was more than a hint of Hogwarts about the place. Sadly, after only one year, we had to leave Liverpool for family reasons and moved to nearby Widnes where I was transferred to another grammar school called the Wade Deacon. As at the Collegiate, I was put into a fast-track academic program, which meant that we didn’t do a lot of things that I would have enjoyed. We did very little art or music. We read plays but didn’t do any practical drama. It was mainly desk study, punctuated by games on a Wednesday afternoon.

When I was 16, a group of friends and I wanted to stage a play and asked a teacher we liked if he’d direct it. He agreed and we worked on it for weeks outside regular schools hours, in the evenings and at weekends. We raised money, printed the tickets, built the sets and made the costumes. We put the play on in the school hall where it ran for three sold out nights. Over the next couple of years we did four plays altogether, I think. The third one was The Importance of Being Earnest, by Oscar Wilde. By then, the teacher who’d been helping us said he didn’t have time to direct it, but had a suggestion. He said, “I think Ken should direct it.” I nearly passed out. I thought, “I can’t direct the play. I’ve never directed a play.” I expected the others to agree but they all nodded and said, “Yes, would you do it?” Given the unanimous vote of confidence, I agreed and loved the whole process.

At the same time, I was under pressure at home to do well at school. Because I’d had polio and wore a brace, I obviously wasn’t going to make a living doing heavy manual work. My father kept saying, “You’re going to have to earn your living with your head and need to focus on your education.” Even so, in my last years at high school I was so preoccupied with exams and putting on these plays that I didn’t have any clear idea about what I was going to do next. The head teacher at the Wade Deacon, Mr. Bonney, had seen the plays and asked me if I’d thought about studying drama or maybe becoming a teacher. I hadn’t. He suggested I apply to a college in Yorkshire called Bretton Hall, which specialized in the performing arts, the humanities and education. They offered main subject studies and professional training as a teacher.

Teaching inspiration

Bretton Hall is a beautiful Georgian mansion in an idyllic, bucolic setting in the heart of Yorkshire. I became a student there from 1968 to 1972, studying English and theater and hanging out with people—students and faculty—that I found endlessly interesting: musicians, visual artists, sculptors, actors and dancers. We were also studying education, working with children and doing professional teaching practice in local schools. We had some wonderful teachers of our own.

One of our philosophy tutors was a piercingly smart Irishman called Victor Quinn. Steeped in Irish literature and European philosophy, he had a voluminous red beard, twinkly eyes, an incisive mind and a keen, puckish wit. You couldn’t get anything past Victor. He was so curious, open and willing to debate. I loved every moment with Victor, and Bretton consciously cultivated those sorts of relationships with the faculty.

We had a young principal named Dr. Alyn Davies. He was a Doctor of Science, urbane, quick-witted, widely read and politically adroit. We got on well and as time went on we talked often with each other. Towards the end of college, I was trying to decide what to do next. Dr. Davies and I talked about PhDs. I felt, as I know many students do, that I could have worked harder at college. I graduated with a good degree, but I was intrigued by the idea of tackling a doctoral program. I had no career plan in mind, just that it would be an interesting challenge, like climbing Annapurna.

Because I didn’t have any money, Dr. Davies suggested I apply for a scholarship. It happened that The University of London was looking for people to research assessment and examinations. I’d benefited a lot from putting on plays when I was at school and so had everyone else who was involved. When I was training as a teacher, I became interested in the history of drama in education, by how much it can benefit kids in all types of school, and why it wasn’t more widely practiced in education.

I put together a proposal for a research project into the roles and value of drama in schools and how it can be assessed, sent it off to the University of London and waited for a response. In due course, I was awarded a scholarship, moved to London and registered as a graduate student. I met wonderful people, including authors whose books I’d studied as an undergraduate. I immersed myself in the life of the university and became especially interested in how the arts in general can be used in to effect social change. Then, by chance, a paid job came up as part of a national project to research the very thing I was studying for my PhD—the place of drama in schools. I got the job and was on my way.

I’ve always been fascinated by people in all their diversity; by how their potential is constrained or fulfilled by culture and especially by education.

I’ve directed local and international projects; worked with governments, corporations and cultural organizations, run research projects, professional development programs for teachers and principals and taught in higher education. I’ve written about the nature of creativity and the diversity of human talent. I’ve written books about school transformation; official reports for governments and put together government strategies. There’s a set of long-term recurrent themes in all my work. I’ve always been fascinated by people in all their diversity; by how their potential is constrained or fulfilled by culture and especially by education. These themes haven’t come from out of the ether. They’re rooted in my own experience of growing up where I did, of going to school where I did, the people I met—people like Charles Strafford, Miss York, Victor Quinn, Alyn Davies and many others.

I don’t claim to have originated all the ideas and principles I promote. People have been arguing for them from ancient days. From the beginnings of mass education in the 18th and 19th centuries, there have been passionate advocates and practitioners of more holistic, humanitarian, progressive forms of education, which take account of the complex creatures we are and of the conditions in which we do best. I’m one of many who’ve taken up that torch. I continue to wave it because the need to act on these principles is becoming more urgent, not less. The nature of education is not an academic debate for me. We’re dealing with people’s lives and it’s vital to get this right.

As told to Top Hat. Transcript edited and condensed for clarity.