Top Hat is the active learning platform that makes it easy for professors to engage students and build comprehension before, during and after class. This interview is part of our recurring series “Academic Admissions,” where we ask interesting people to tell us about the transformative role education has played in their lives.

Born and raised in the freewheeling environment that was 1960s Berkeley, California, Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa learned early on the importance of diversity and transdisciplinary thinking. Undergrad at the convervative Boston University forced her to seek out students from different backgrounds to build a community, while grad school at Harvard allowed her to pursue big picture thinking surrounding the way people learn.

A pause from institution-based academia took her to Quito, Tokyo, Geneva and back, all of which influenced her thinking on multilingual learning and the intersection surrounding the mind, brain, health and education. A proponent of online learning—having completed her PhD through Capella University—Tokuhama-Espinosa is currently a professor at Harvard University Extension School and conducts educational research with the Latin American Faculty for Social Science in Ecuador in Quito on the integration of mind, brain, and education science into teachers’ daily practice and professional development.

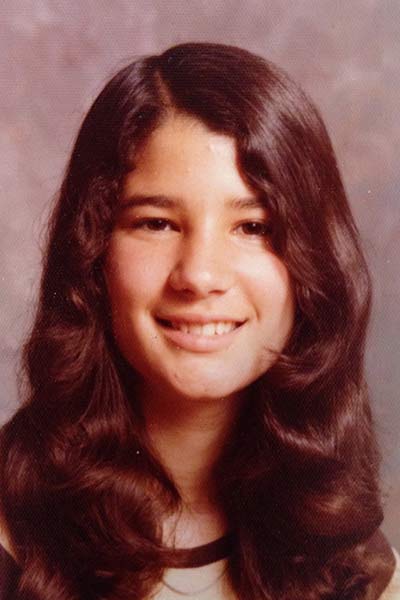

I grew up in Berkeley, California, in the 1960s. My Japanese dad and Irish mom met at UC Berkeley and eloped. I was born in their first year of college, and my two sisters shortly after. It was a different kind of place to grow up. It was open, free—everything was okay. My best friends were Kimberley, who was black, Tammy, who was Japanese, and Lori, who was redheaded. We palled around and nobody even thought about the differences between people. It was just the way things were.

My dad went to UC Berkeley on a nuclear physics scholarship, but of course, in the ’60s, that was not a thing to do. So he chose to teach math in the public sector for the next 40 years, to work in the poor neighborhoods, and in the really hard schools. My mom started off in biology but ended in linguistics, and studied what was then called Ebonics—the African-American vernacular English language. I remember being schlepped along by my mom to her classes when I was about five, and being in charge of my sisters who were four and two. We would color and find ways to keep busy in the back of the rooms. It took my mom 10 years to graduate. But I got to go to UC Berkeley when I was five.

Berkeley was an amazing place. You’d step outside of the classrooms, and there were street entertainers, marches, people asking for you to sign on and to be a part of a protest. It was just an incredible place to grow up. But like a typical teenager, when it came time to think about college, I looked at the farthest point away on the map. And that was Boston.

‘What is intelligence?’

Boston University was huge, and you could find any kind of subgroup that you ever wanted to be part of. But it was also conservative. I got a job in the international student office because I was really craving a little bit more variety in things. I started off in communications, thanks to a high school counselor who said to me, “I was told that you’re really strong in communications. Have you thought of doing something with photo journalism or these other things that you seem to like?” I didn’t know what I wanted to do or who I wanted to be, but to have one person tell you, “Hey, I think you’re good at this,” well, it tipped me completely.

I decided to do a second major in international relations because I thought it’d be helpful if I was going to be a Nat Geo photographer and travel the world. One degree was a BSc, one was a BA, and the people in each program were totally different. I was active in the student government and also in an anti-apathy campaign to try to get people to be part of a community. I lived for a while in the residence system on the communication floor, so I met all the younger students coming in from all kinds of backgrounds.

I went straight from undergraduate to grad school at Harvard where I did a master’s in international comparative education—it essentially combined communications and international relations through my growing love of education. Jane Etish-Andrews, the director of BU’s international students office, led a different vision of education nurtured from people’s perspectives from different countries, and that was hugely influential to me. I became fascinated by how people get other people to learn things. I was trying to figure out what people consider smart in different countries. What is intelligence? How did people choose what to teach—how many hours of math or science or language? Because in Berkeley, in the preschool system, our curriculum was incredibly, naturally, transdisciplinarian. Our literature teachers did talk to the history teachers, who did talk to the math teachers, who did talk to the photographer teachers…it was not as siloed as subjects are today.

Exploring multilingualism

https://www.instagram.com/p/BWax7E1hlw5/

After grad school, I was hired by the Colegio Americano de Quito, which is the American school in Quito, Ecuador. My boyfriend, whom I met in college, was already there working as a diplomat, but two weeks after I was hired, he was awarded a scholarship to study in Japan. Taking him out of the equation was wonderful, because it allowed me to figure out if I liked this place for this place, if I could make my own friends, if I could have a space here. I was working with high school kids and I was only about five years older than them. It was a baptism-by-fire situation. But it was fantastic, an incredibly interesting culture shock, because of what the appropriate etiquette within a classroom was there, the formalization of things that were totally different from what I experienced in Berkeley or Boston.

I learned there that the biggest changes you can make in a person in regards to education are attitudinal. It’s not so much the knowledge gaining or skills, it’s the attitudes that you can shift in people that makes a big difference.

My boyfriend and I married, and we were sent to Japan, so my next teaching job was in an international Catholic school in Tokyo, working with fifth, seventh, 10th and 12th graders. I was in charge of the values class. We studied the six biggest religions in the world, and we learned that there’s only one rule that’s the same for all of them: do unto others as you would have them do unto you. It’s the golden rule. There are some things in education that you can boil down to a single common denominator of humanity, which again goes back to that idea of the international comparative education. What is it that we all value? It’s still fascinating to me.

After Japan we were back in Quito for about four years, and I continued to teach. Then my husband was posted to Geneva. By this point we had three young children, and I began to look into multilingualism, how people learn foreign languages and how it changes how you can think about things—the neural underpinnings. Well, it was a total experiment with my kids. The first book I wrote, in 2000, was called Raising Multilingual Children (I then wrote two more books on the subject). I spoke English to the kids; my husband spoke Spanish. They went to a German school, but the environment was French. During this time, I was able to meet a lot of the great leaders in the neurolinguistic field and I spent the next decade focussed on language and the brain… because language mediates all other learning.

Learning online

After six and a half years in Switzerland, we returned to Ecuador and I got a job at the San Francisco de Quito University. I started an institute for teaching and learning with the goal of opening it up to the public so that all school teachers could have access to the pedagogical resources. But soon after there was a change in the laws that required all university instructors to have a PhD—my master’s wouldn’t cut it. My husband was also being sent to Peru for two years, so the university suggested I use that time to get a PhD.

I looked into the options for study, and was guided by some colleagues to Capella University. This was 2006, and the general perception at the time was that online education was of lesser quality than face to face. Honestly, I was totally skeptical about it too. But let me tell you, I interviewed with them, and I was stunned because it was a harder process to get in, and then to do well in, than my program at Harvard. That’s because at Capella they knew they were being held up to higher scrutiny. They had to be more stringent, have more courses, offer a more intense experience. And I quickly learned that it was as hard as I decided to make it. I had inspirational teachers. I had personalized learning experiences. I said, “I want to look at mind, brain, health and education. I want to look at this conglomerate, this transdisciplinary vision”—and they let me do it.

Capella University. Photograph: Bobak Ha’Eri, CC-BY-SA-3.0

Here’s a testament to how good Capella is: my doctoral thesis, which is almost 700 pages long, had four publishers offer to turn it into a book, even before it was published, even before I graduated, because it was such a rigorous study. It was a grounded theory analysis of all the information available in brain-based learning using the Delphi panel—experts around the world passed judgment on what they thought was good information for teachers to learn about the brain. I had key people in the field like Howard Gardner and Kurt Fisher and Mary Helen Immordino-Yang on my panel, chiming in and confirming what I was saying. That was a fantastic experience. And I was able to publish two books about ways to improve teachers’ pedagogical knowledge through advances in neuroscience from my thesis.

Back to Harvard

In 2012, I was invited to be a co-teacher in a Harvard class on mind, brain, health and education, along with two neuropsychologists. That worked great until 2015 or 2016, when Harvard said, “Look guys, the demand for online learning is so big now, and we need to do more online courses. We’d like to know if you would be willing to be one of the first courses that we put 100 percent online.” I said “yes,” and the other teachers said “no.” So I became the lead teacher, which was fascinating.

My course was then selected by Harvard as one of three courses that they showcased to new teachers to say, “This is the instructional design that we’re looking for. This is the clever way to leverage quizzes, to reinforce vocabulary and concepts, to use discussion boards to create a community. And this is the clever way to use bundles and mini libraries, so you can differentiate entry points for different students. This is the way that you have a rewrite policy so people learn from their mistakes and improve in the project over time.”

I was given a nice recognition for having tweaked an instructional design, and I credit my amazing experience at Capella. I tried to take the best things of what I knew about how the brain works, and apply that with what I understood about technology. I was asked to be on the OECD expert panel to address how neuroscience influences learning. The recommendation of the entire commission after two and a half years of meeting was that teachers need more neuroscience and they need more technology. And that was exactly the space that I was working in. And luckily there were powerful people at Harvard who just said, “This is the future of education, this is the way it’s going to go, so let’s do it right.”

That course confirms everything I’ve always wanted in education: it allows me to teach students from all these different countries and clashing viewpoints, and get them in the same virtual classroom to talk about fascinating things.

Neuro-constructivism in action

My most recent book is an overarching theory of how humans learn. The idea of the Five Pillars of the Mind was borne of this crazy-interesting concept of neuro-constructivism: people construct knowledge based on prior experiences; they scaffold higher level concepts onto lower level concepts. And technological advances allow us to actually see neuro-constructivism at work in the brain.

We’re so used to thinking of school being divided by subject areas, we don’t even stop to think about how dumb that is

That goes right back to the sandbox in Berkeley, California, when I was three. The beautiful thing about the education I began with was that nobody said, “This is math, this is language.” They said, “Look at your world. Connect the dots if you can. Do whatever interests you.” Everybody encouraged my creativity, and they criticized us to help us be better, but nobody ranked us. We didn’t have standardized test scores that we lived and died by. We were just motivated to explore the world in different ways.

We’re so used to thinking of school being divided by subject areas, we don’t even stop to think about how dumb that is. We get into this mindless routine in education, and this is exactly why we have the problems we do. We continue to think that standardized test scores are a reflection of intelligence. They’re not. We continue to divide by subject area or kids by age. We do things that are totally contrary to the evidence we now have about how humans learn. But I actually think this is the best time in the world to be an educator, because we’re riding a wave that’s about to crest and tip into another space for education.

For the first time, public opinion has shown that online learning is superior to face-to-face. We’re finally hitting the point where there’s more resources, there’s more differentiation, there’s more freedom and time. People share more. Right now, we have never had a better educated population, we have never had more tools to educate with, and we’ve never had a better understanding of how we learn. So long as we can leverage all that together, we’re in a wonderful place.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.